Bishop Porteus and transatlantic slavery

In their role as Bishop of the Colonies, the Bishops of London had a direct connection with the Americas (America and the Caribbean), where enslaved persons were forced to toil on plantations to produce commodities such as cotton and tobacco.

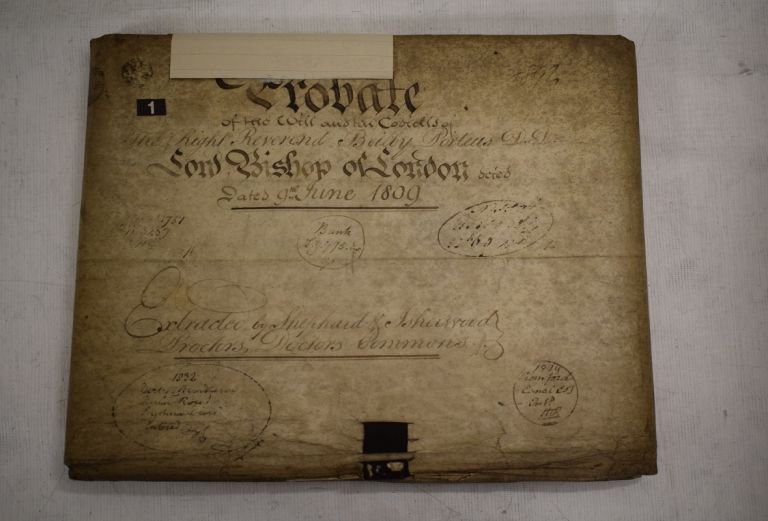

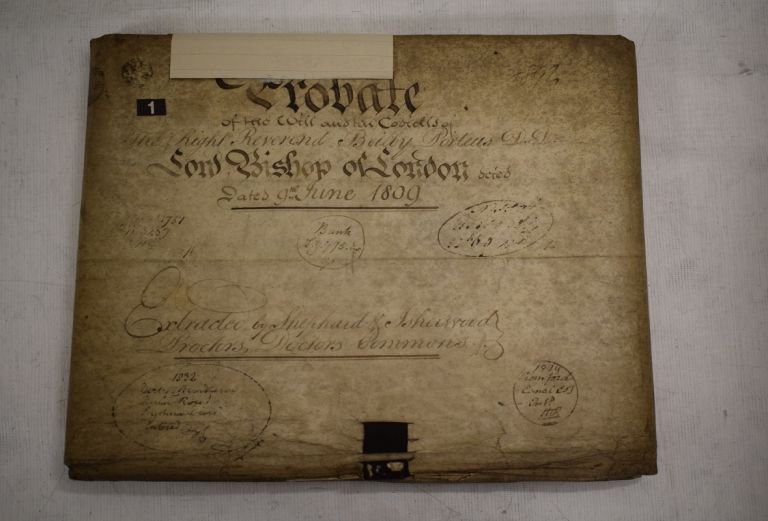

The son of Virginian tobacco plantation owners, Bishop Porteus (b.1731 – d. 1809; Bishop of London 1787-1809) directly benefited from the transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans. The family had returned to England by the time Porteus was born, but they continued to receive income from their plantation in Gloucester Town, Virginia, worked by enslaved people. Porteus and his brother inherited the land in 1758, to manage and then sell, with the proceeds going to them and their siblings.

Fulham Palace is now actively researching the Gloucester Town plantation and the enslaved people who were forced to worked there.

Although Porteus and his family had direct links with slavery, in his adult life he was active in campaigning for the better treatment of enslaved people.

Bishop Porteus’s literary and social circle included the reformer Granville Sharp (1735-1813), Reverend James Ramsay (1733-1789), the writer and moralist Hannah More (1745- 1833) and the parliamentarian William Wilberforce (1759-1833), all of whom were vocal and influential opponents of the slave trade.

Possibly influenced by James Ramsay’s first-hand accounts of the barbarity of enslaved labour in the Caribbean, Bishop Porteus appealed in a pamphlet published in 1784 to the Church of England to manage their plantations in Barbados with humanity and enlightenment. He made use of his position within the House of Lords to promote measures to abolish the slave trade and throughout 1806 and 1807 supported the passage through the House of Lords of the bill which brought an end to the transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans.

It should be noted, however, that Bishop Porteus was not initially an advocate of the abolition of the slave trade and his family continued to profit from the exploitation of enslaved people throughout his life. In his will he made provision that land in Port Tobacco, Maryland, belonging to his late brother, should stay with his brother’s widow, Martha Porteus, and then pass to his great-nephew, Thomas Porteus. This land was worked by enslaved people. A 1790 census return shows that Martha Porteus had nine enslaved people living with her.