Alexis Haslam, community archaeologist

So, the results are in and we have a name for the mouse featured in our wonderful new book ‘The Palace Cat – Adventures in time at Fulham Palace’. A great read it is too, as Edmund the cat leads our intrepid young time travellers Matilda and Tom through a whistle-stop tour of the Palace’s history and the intriguing characters who have graced the site over the years.

For those of you who don’t know Edmund (and I genuinely can’t believe any regular visitors to the Palace haven’t met him) he is of course our very own cat. A solid member of the garden team he can usually be found roaming around the walled garden, welcoming in visitors when the gates open and generally making himself known, especially when there’s a camera to flirt in front of. He is named after Bishop Edmund Bonner, otherwise known as ‘Bloody Bonner’ who was rather keen on torturing heretics.

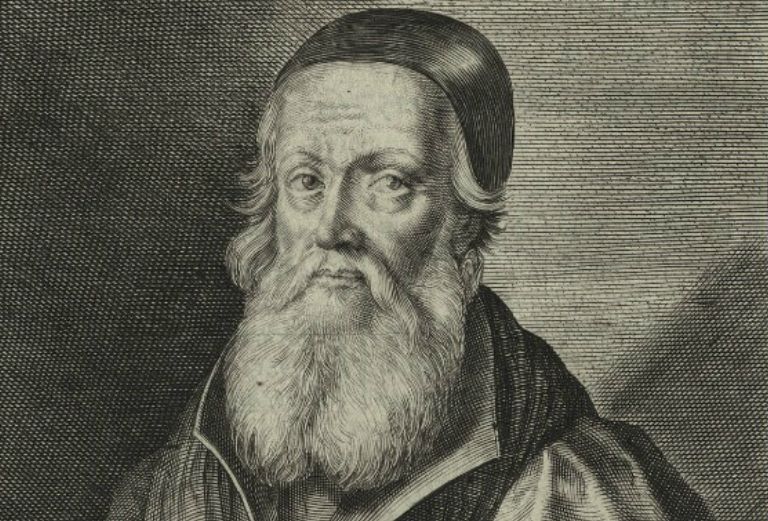

Bonner served two terms as the Bishop of London; the first between 1539 and1549. He was subsequently deprived of his position in the Star Chamber, yet he returned to the Bishopric under Mary I between 1553 and 1559. It was during his second term in office that he became particularly keen on stamping out religious dissent as Catholicism once again became the religion of authority. Foxe summed him up somewhat succinctly in his book of martyrs:

‘This cannibal in three years space three hundred martyrs slew

They were his food, he loved so blood, he sparèd none he knew’.

Indeed, Fulham Palace became a bit of a scary place to be summoned to under Bonner. It was in the great hall that he sentenced ten Essex men, two women and a Dutchman to be burnt at the stake and he was rather partial to sitting in a chair at the end of a path known as the ‘Monk’s Walk’ and casting judgment on those sent before him. I wondered if anybody would choose the names of Henshaw or Willes for the mouse, two young men who didn’t particularly enjoy their ‘turn about the garden’ as it were.

Still, in all honesty Edmund the cat isn’t exactly brilliant in his stated position as ‘chief pest controller’. The fame went to his head some time ago and there are no mice in danger at the Palace whilst he’s on patrol. Bloody Bonner? Bloody useless Bonner more like. He’s the face of the Palace and he likes it that way. Maximum appreciation with very little effort!

We received numerous nominations for the name of the mouse and rather aptly Grindal was chosen. You can spot the cheeky little chap in all of the scenes in the new book hiding away, not that he really has anything to fear from Edmund.

So who exactly was Grindal and why is he a significant character at the Palace? Well, Edmund Grindal was born in Hensingham, Cumberland in 1519. After graduating from Cambridge he became chaplain to Bishop Ridley in 1551and was made Precentor at St Paul’s Cathedral before becoming chaplain to Edward VI. To say that the 16th century was a tad partisan in terms of religious doctrine might be a bit of an understatement. In working with Ridley and Edward, Grindal had certainly thrown his lot in with the Protestant movement which did not work out too well for Ridley. Following the death of Edward, Ridley put his support behind Lady Jane Grey. With the succession of Mary I he was burnt at the stake in 1555.

Deciding it was best not to hang around and wait for his turn on Bonner’s barbecue, Grindal fled to the peaceful sanctuary of Switzerland. He returned on Elizabeth’s coronation and was made Bishop of London in 1559. But it isn’t really for his religious leanings that we’re rather keen on Grindal at the Palace.

Over the years there has been many a green-fingered Bishop of London, with Henry Compton of course being our best-known botanist. As far as I can decipher the first formal arrangement of the Palace gardens appears to have been established under Bishop Fitzjames (1506-1522), yet the first Bishop we know to have been passionate about plants is Grindal. He is believed to have introduced the Tamarisk tree to England, bringing one over from Switzerland and planting it at Fulham where

‘…the site being moist and fenny, well complied with the nature of this plant’ (Fuller).

The most famous Grindal tale involves his vineyard at the Palace. It is interesting to note that whilst the 16th century appears to have been fairly warm, the 17th century was anything but, and viticulture pretty much died a death in England. Yet in the middle of the 1500’s things were fairly temperate and Grindal was successful in producing grapes. Indeed, it was somewhat of a Tudor tradition to send gifts of fruit grown within your own grounds as a means of extending the hand of hospitality and friendship. Grindal certainly sent grapes from Fulham to his friend Sir William Cecil. He also sent them as an annual gift to Elizabeth I, yet in 1569 things went somewhat awry.

Grindal duly sent his grapes to the Queen, but rumour abounded that one of his servants had recently died of the plague at the Palace and that three more were sick with it. In sending the grapes he was accused of endangering Elizabeth’s life. Grindal started to panic about those barbecues again and wrote a letter to his friend Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief advisor, stating that one of his servants had indeed passed away. This however, was not as a result of the plague he said, but of a ‘flyx’ which nobody else had contracted and he had not deemed a threat to her majesty.

Fortunately this explanation seems to have been accepted as in 1570 he was made Archbishop of York and then Archbishop of Canterbury in 1575. Yet upon reaching the highest religious position in the land he fell out with Elizabeth again, this time over ‘prophesyings’ which Grindal refused to suppress. Perhaps it was a case of sour grapes over the previous incident although I’m sure Grindal had his raisins for sticking by his principles. He eventually apologised to the Queen but died in 1583 with, according to Daniel Neal, the reputation of ‘one of the best of Queen Elizabeth’s Bishops’.