Written by historian and researcher Nadege Forde-Vidal.

As part of our Black History 365 programme, we are delighted to welcome social historian Nadege Forde-Vidal to Fulham Palace to share her research in a special talk, Black Gardeners of West London. In the lead-up to the event, Nadege shares her journey of discovery exploring the extraordinary life of Toby Eccho, his family, and his connection to some of the most renowned gardens of 18th century London.

Her blog below offers a fascinating glimpse into her research journey and the lasting legacy of Black horticultural knowledge in west London.

Last year, I was contacted by a community group looking for stories from the past about people of African heritage living and working in Brent. This type of work I find most rewarding – seeking out traces of those whose lives have remained hidden for centuries – but the greatest joy comes in sharing those stories, as they enable people of all ages, cultures and backgrounds to build a stronger connection to their community and landscape.

In the spirit of sharing – everyone and anyone with internet access can do this sort of research, and I encourage them to do so. Sure, it takes time, and some commitment but the more you do, the more you learn. Digitised documents can be found everywhere, and are steadily growing in number, with better public access – a glorious network of treasure troves containing thousands of untold life stories – and with more information made available daily, what we can know is always changing.

I have used various online archive collections for this sort of work before but with just a location to work with (and taking into consideration the fact that the borough of Brent is a relatively recent creation) only genealogy sites held any real potential as they enabled me to search Brent’s parishes one by one. With no more to go on, I searched each parish for specific words used to identify people of African heritage at the time. Within hours, I found a baptism record for a Sarah ECO at St Mary’s church, Willesden that recorded her father’s name as Tobias, and described him as ‘a Black’.

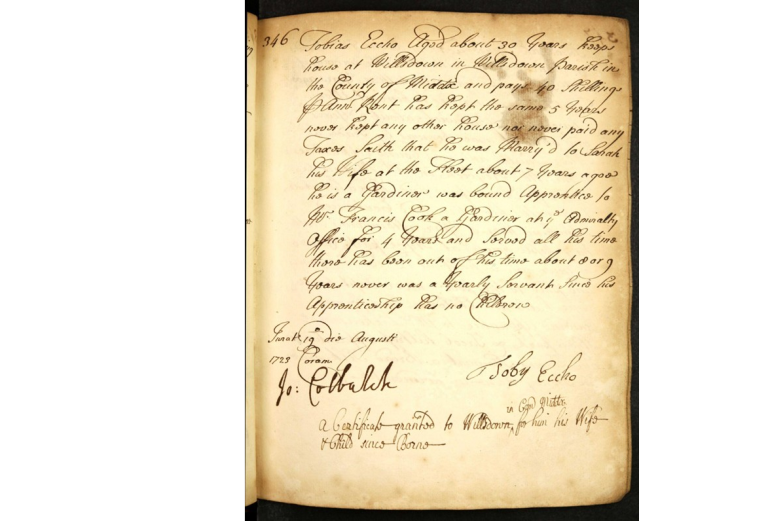

Hoping for more details and now equipped with a name (an unusual one at that), I had the tools to dig deeper but did not anticipate the number of different spellings of Tobias’ surname (eight so far). After a few attempts, a Westminster parish settlement record from the London Archives popped up containing the name ECCHO. It provided incredible detail of Toby’s life up to the birth of his first child, Sarah in 1723.

The settlement records of 1723 confirm that Toby, a free Black man in his early 30s, was acknowledged as a member of the parish of St Martin’s in the Field by local authorities. This document gave him, and his wife and family, a promise of support from the parish if they fell on hard times, even if they chose to live elsewhere.

We learn that as a young adult, Toby had secured an apprenticeship with a professional gardener named Cook from the parish of St Martins, before people of colour were barred from doing so, which suggests he had been in the area for some time and already possessed some knowledge of plants and cultivation advantageous to Cook.

Becoming an apprentice marked a profound break in a youth’s legal, economic and social position, … they were subject to the authority of their employer, no longer dependent on their family for food and lodging, and on the path to acquiring the skills and income that would allow them to establish an independent household of their own when the time came.

Toby Eccho (Leaving Home and Entering Service: The Age of Apprenticeship in Early Modern London by Wallis, Webb, & Minns. 2009, pg 3 - 4)

Toby served his four-year apprenticeship in the Admiralty’s botanical gardens by St James’ Park, where his plant knowledge would be tested by the flow of exotic flora arriving onboard Royal Navy ships. Admiralty records may still provide further details of Tobias’ activities and the plants he may have cared for during his four-year tenure.

Within a year of completing his apprenticeship, Toby married a young woman called Sarah Williams from Watford. In the marriage record, he describes himself as a Chelsea Gardener.

The only gardens of any significance in the area at the time were of course the Chelsea Physik Gardens (now Chelsea Physic Garden), founded by Sir Hans Sloane for the precise purpose of exploring the medicinal values of plants. The first heated green house (stove) was built in 1680 for the care of medicinal exotics and an international seed exchange was established in 1682 that brought the world’s flora to Chelsea. As a result, Chelsea and much of West London, became a hub for seed and plant nurseries throughout the 18th century.

Many plants and seeds from Africa were brought to the gardens of West London, especially those that had medical potential or were deemed profitable in some way.

The plant exchanges, botanical gardens, and scientific societies that accompanied the European enlightenment drew upon the botanical resources of those they colonised and enslaved…[and] West-central Africa has one of the most highly developed ethnomedical traditions.

Dr J Carney (African plant knowledge in the circum-Caribbean region. Journal of Ethnobiology 23(2):167-185. 2003)

African children, like most children in the world at that time, assisted with the field crops and village gardens that provided vegetables, herbs and medicinals. Knowledge of how plants were cared for, and what their uses and benefits were, was passed down from generation to generation at a young age. This inherent understanding made Toby a particularly valuable employee for his familiarity with many of the medical plants under cultivation.

Toby and Sarah moved north to Willesden away from the toxic air of St Martins. They found themselves a small property at 40 shillings a year surrounded by nature at its most fertile. Given his skills and experience, Toby was well suited to work in any of the plant and seed nurseries or market gardens that dominated the landscape of West London. By the time they were expecting their first child, they had been in Willesden Green for 5 years. Named after her mother, Sarah Eco is the first known child of African heritage to be baptised in Brent.

Though little is known about Toby’s life prior to his apprenticeship, we do now have some insight into his interests, career and family life. And though he died relatively young at the age of 44 in 1737, his children and grandchildren continued his legacy by working in West London’s gardens for generations to come.

Toby Eccho’s story is just one of many waiting to be uncovered. Join us at Fulham Palace on Wednesday 23 July for the free talk Black Gardeners of West London as Nadege Forde-Vidal shares more of her research into the lives, labour and legacies of Black people who shaped London’s green spaces. This is a unique opportunity to discover a new perspective on the history of gardening, landscape and belonging.

A recording of this talk is available on the Fulham Palace YouTube channel.

About the author

Nadege Forde-Vidal is a London based social historian and researcher who collaborates on a number of local history projects with heritage sites, archive repositories, community groups and schools.

Nadege created the Sankofa London schools Project in 2021 to bring research skills and hidden histories of people of colour to the classroom; is the Lead Historian for the Black Chiswick through History project, produced learning resources for Hounslow Council Black History Month, and co-produced Hounslow Action for Youth, Botanical Women of Hounslow project.