Alexis Haslam, community archaeologist

Well, I suppose it’s time I gave this a go, isn’t it? I have to be honest and say I’ve always found the Viking link to Fulham somewhat tenuous. The story has gone on to form part of Fulham folklore however, with a Viking ship displayed on the coat of arms of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and of course in various guises of the Fulham Football Club crest. Let’s face it, I’m going to have to confront those Vikings at some point aren’t I? Now seems as good a time as any.

So, where does this all begin? Well, one of most useful articles I have found available is by John Baker and Stuart Brookes. Entitled ‘Fulham 878-79: A New Consideration of Viking Manoeuvres’, this piece appeared in the journal Viking and Medieval Scandanavia, Vol. 8 in 2012.

The story is quite straightforward. In early AD 878 a Viking army led by Guthrum, King of the Danish Vikings under the Danelaw, invaded Wessex, forcing the region’s King, Alfred, into hiding in the Somerset marshlands. Alfred and his army rallied in the spring defeating the Viking army at EÞandune (possibly Edington, Wiltshire), and Guthrum had to retire to Cirencester in the autumn. At around about the same time, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that another Viking force arrived in the Thames and encamped at Fulham. These two groups hung around for a couple of years, with Guthrum’s force eventually settling in East Anglia and the Fulham Vikings departing for Gent to begin raiding on the other side of the channel.

So there we have it. The Vikings came to Fulham for a couple of years, leaving their mark in the history of the Borough and creating the legend which continues to this day. What do I think of this from an archaeological perspective though? Well to begin with, as a collective us archaeologists do like a bit of evidence. So, as the on-site conversation might go:

Supervisor: So, what have we got then?

Archaeologist: Naff all Sarge.

That’s right. We have absolutely no physical evidence of these Vikings whatsoever. Not so much as a fragment of pottery. Add that to the fact that we are talking about the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle here, a collection of annals which were copied multiple times by different monks, most probably inebriated and writing in poor candlelight, and which were still being updated in 1154. The margin for error here is huge.

Still, we all like a theory, so back to Baker and Brookes. The assumption has always been that the Fulham Vikings were a major army, which the Welsh monk Asser described as a ‘great army of pagans’. An army that arrived to support Guthrum and pose a direct threat to Alfred and Wessex. Is this true though? The Chronicle describes the Fulham army in AD 879:

‘7 Þy geare gegadrode on hloÞ wicenga, 7 gesæt æt Fullan hamme be Temese’.

This translates (apparently) as:

‘And that year a gang of Vikings gathered and settled (sojourned?) at Fulham on the Thames’.

Work by Christine Fell on the language used here is particularly interesting. She suggests that the term ‘wicenga’ is unusual and refers to a group of pirates as opposed to an army. The term ‘hloÞ’ is also important, meaning band or company as opposed to ‘here’ which is used to describe Guthrum’s army. This all appears to suggest that the Fulham Vikings were a smaller group who were perhaps using Fulham as a muster point, awaiting the arrival of further companies and recruits. By the time they departed they could of course have become a much larger unit.

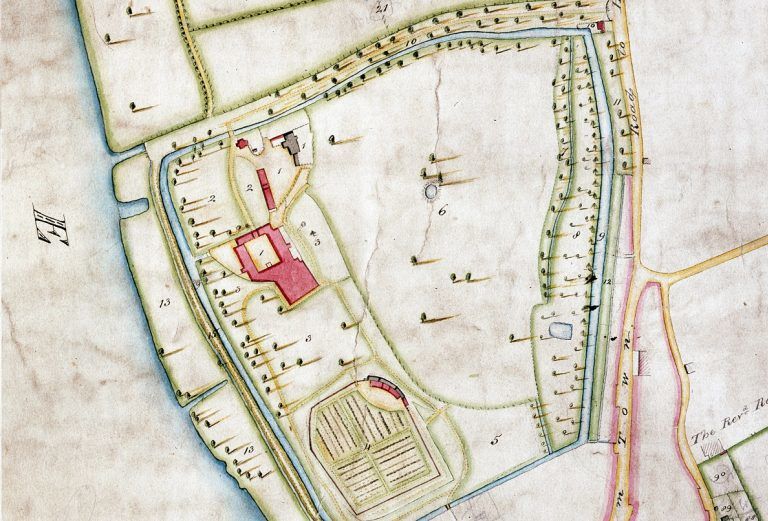

But where are these Vikings? Where in Fulham did they settle? Here again, from the archaeological angle, the lack of evidence is really frustrating. We shouldn’t forget however that when compared to the Romans, the Saxons and Vikings weren’t quite as into making pots. This means that you’re much less likely to find material associated with their presence. Other items used such as leather and timber would not last on Fulham’s free-draining sandy soils. It has long been suggested that the Vikings may have settled in the area we call the Homestead Moat, which is on the Fulham Palace site where the nursery is currently situated.

I’m going to suggest something else though, seeing as I can’t get much further than theory without that physical evidence. When Viking armies settled they tended to undertake fortification work. These were often ‘D’ shaped, and the example at Repton in Derbyshire used by the Great Army during the winter of AD 873-4 is a classic. Encompassing an area of 1.46 hectares on the bank of the River Trent this encampment comprised a large bank and ‘V’ shaped ditch which incorporated an Anglo-Saxon Minster (now the parish church of St Wystan). Although the use of waterways and estuarine islands as encampments was common, the concept that the Fulham Palace moated site was used is somewhat far-fetched. At 15.5 hectares the site is simply far too big.

This has led me to looking a little bit more closely at our neighbour, All Saints Church. How old is this church? Well according to Feret, up until 1631 when St Paul’s was built in Hammersmith, All Saints was the only church in the two parishes. Fulham Palace Road was even known as ‘The Churchway’ at the time as people had to travel down it in order to worship. The oldest part of the church that we see today is the tower, which is understood to have been built in about 1440. The rest of the church was constructed by Sir Arthur Blomfield (son of Bishop Charles Blomfield) between 1880 and 1881. Interestingly, Feret reports that during the construction of the current church they discovered the foundations of three earlier versions, with the earliest footings dating back to possibly the 12th century.

If that is true then the origins of All Saints go back to at least the 1100s, and there is supposedly a record of a tithe dispute concerning the church in 1154. Sadly, revolting peasants trashed the building in 1381 and destroyed all the records in the process. At this point however, we do have some archaeological evidence. Between 2015 and 2016 Pre-Construct Archaeology undertook an archaeological excavation at 84-90b Fulham High Street.

Here they not only discovered the Fulham Stream which ran roughly along the current line of Fulham High Street (filled in by the 18th century), but also a 17th century wall. This wall had been constructed from re-used material, much of which appeared to come from a major ecclesiastical building. The stonework mostly dated to the later medieval period, and this may relate to the version of All Saints destroyed during the Peasants’ Revolt. Interestingly however, Quarr stone, which derives from the Isle of Wight was also present. This is fairly unusual in London and is normally associated with high-status Saxo-Norman buildings, such as the White Tower at the Tower of London. This information may suggest that All Saints has even earlier origins, possibly in the form of a Saxon Minster.

So you can probably see what I’m getting at here. If I were a Viking travelling up the Thames looking for a good spot with the potential for a bit of looting, a nice church on a moated island would probably tick most of the boxes – just like St Wystan’s in Repton. But what about that D-shaped enclosure? Well, that excavation in 2015-16 found part of the moat which surrounds the Palace that Lucy our head gardener has named the ‘churchyard stretch’. Running between the Palace grounds and All Saints, this part of the moat is incredibly straight, but when looked at in plan with the Fulham Stream it forms a rough ‘’D’ shape, enclosing an area of around 1.95 hectares and of course, All Saints church.

Now the earliest pottery recovered from this ditch dates to between 1270 and 1350, so this theory might be a tad fanciful. But if you’ve got a better idea we’d love to hear it. There’s Norway we’ll really know until we find some of that physical evidence!