By Alexis Haslam, community archaeologist

For those of you who use the churchyard entrance as your main route into the Palace, you will have been somewhat inconvenienced by the closure of the gate over the past couple of weeks.

With spare cobbles aplenty after the recent driveway works it was decided to replace the rather unattractive concrete slabs that linked the churchyard to our lovely new Breedon gravel path. Given the wonderful work the gardens team and volunteers have undertaken in clearing, grassing and planting the previously overgrown churchyard bank, the decision was made to build a new cobbled path. This would aesthetically add to what is now an almost unrecognisably improved part of the site.

So a straightforward job then. Lift the horrible old slabs and set some of those lovely cobbles we ‘inherited’ (at great cost) from Kings Cross. Like everything at Fulham Palace however, nothing is quite that simple…

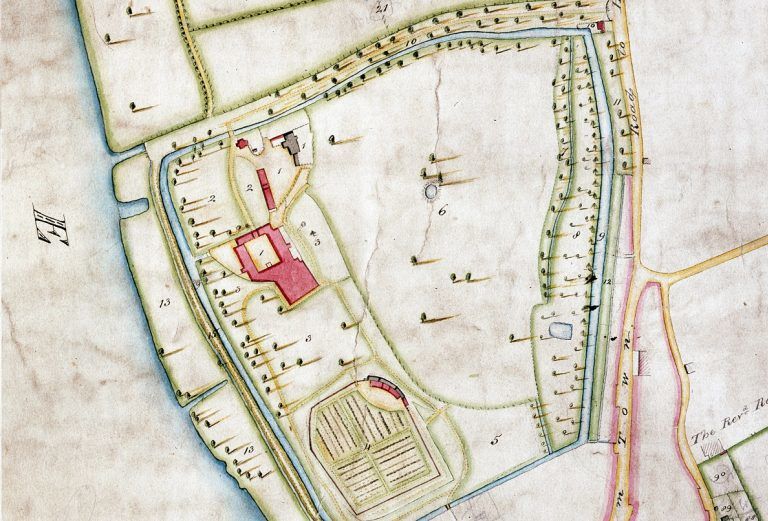

Initial investigations as we moved the large signpost to this area suggested that there was a considerable void beneath the concrete path. Surely not a good thing from a health and safety perspective! Why would this be the case though? The moat which once surrounded the Palace did of course run across this area of the site, yet it was backfilled in the early 1920’s. Filled with builders’ rubble and waste, there really shouldn’t have been any voids at all. In most areas the moat is actually overfilled, which is why the ground is raised along the churchyard stretch.

A quick dip into the history books though, and you’ll find that the Palace has been linked to All Saints for quite some time:

A mote encompassing all the fore cited premises… over which two footbridges on the south side and a horsecart bridge on the west part thereof.

The Parliamentary Survey of 1647

The horsecart bridge refers to the bridge linked to the main drive, but there were evidently a further two bridges over the moat. This still appears to have been the case in 1738-9 when the moat is referred to as being crossed by two footbridges and one great bridge. Writing later, in 1900, local history writer C.J. Feret records only two bridges over the moat – an ornamental stone bridge at the southern end of Bishop’s Avenue, and a drawbridge near the north-west corner of the churchyard. So, by the early 20th century one of the bridges had gone, leaving only the main bridge and the churchyard bridge. All of this evidence points towards the churchyard entrance being a very old thoroughfare.

As soon as the concrete slabs were lifted it was obvious that an iron structure remained beneath surface. This was formed by two large parallel ‘I’ beams, with a series of associated cross beams and connecting iron rods. These had been used to support cast concrete slabs which were overlain by a rubble infill. After punching through one of the slabs with a pneumatic drill, it became apparent why we had a void beneath. The iron and concrete structure was the bridge between the Palace and the churchyard which remained standing when the moat was filled in. As the pouring of rubble could not completely fill the gap beneath the bridge, the space remained.

Of course, voids and structures are all very exciting for archaeologists, but I think when Sian caught me sniffing a lump of the concrete beneath the bridge she became somewhat concerned. I can explain though, honestly! The earth was very humic, which is a smell anyone who has ever excavated a cemetery will know well. The proximity of the churchyard to the Palace has always had me wondering if the boundaries were ever encroached upon. It really was a case of ‘I smell dead people!’ Fortunately, other than a pervading whiff there is no sign of any of our slumbering neighbours creeping into the Palace grounds.

Returning to the bridge though, the structure survived in poor condition. It was decided that the concrete and tie beams would need to be removed and the void filled in before the cobbles could be set. The question remained however; how old was our bridge? Feret’s allusion to a drawbridge suggests that this structure post-dated 1900, but cannot have post-dated the early 1920’s when the moat was backfilled. This suggests that it was almost certainly built by Arthur Winnington-Ingram, presumably because the old drawbridge needed replacing. It is also possible that it was constructed for the anticipated crowds for the church pageants which were held here in 1909 and 1910.

The works are now complete and the cobbles have been laid, so the gate is once again open. The main beams of the bridge can however still be seen on either side of the path, so the next time you cross the churchyard gate, remember that you are walking a well-trodden path, although you no longer need worry about falling into an underlying hole!