by Elowyn Stevenson, front of house supervisor

Our newest temporary exhibition in Fulham Palace museum comes to us from Sir Hans Sloane’s Vegetable Substance collection housed at the Natural History Museum.

Sir Hans Sloane was quite a fascinating and well-educated character. Born in 1660 in Killyleagh, County Down, Northern Ireland, he spent his youth fascinated by flora and fauna which set him up for a life-long passion for collecting and studying the natural world.

Sloane moved to London to study chemistry with the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, and botany at the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1679 where he learned the ins and outs of the human body. This set him up for a prosperous career as a physician. Among his friends were John Ray, the celebrated English naturalist, and Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry. Sloane toured France, met more famous botanists, and was inspired by their collecting habits. After receiving his Doctorate of Physics he returned to London and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1685. He would later become the Royal Society’s Honorary Secretary and President (taking over from Sir Isaac Newton). As if that wasn’t enough responsibility, he was also made a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians two years later!

As well as his work in London, Sloane was able to combine work and travel in a rather dreamy way. He set sail for the swaying palms of Jamaica to become the personal physician to Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle and newly appointed governor of the island. During this time, Sloane collected over 1,000 plants specimens and made detailed notes of local customs and nature which formed the basis for his enormous 7-volume Catalogus Plantarum of 1696 (these same dried plant specimens are still pressed in its pages in the store of the Natural History Museum today).

Upon the Duke’s death Sloane found himself back in London and set up a very successful medical practice – so successful, in fact, that Dr Sloane became the Physician Extraordinary to Queen Anne and King George I, and a slightly less glamorous Physician in Ordinary to King George II. If that wasn’t enough to secure him fame and fortune, he is also credited with being the creator of drinking chocolate!

(From his Wikipedia page: ‘Sloane encountered cacao while he was in Jamaica, where the locals drank it mixed with water, though he is reported to have found it nauseating. Many recipes for mixing chocolate with spice, eggs, sugar and milk were in circulation by the seventeenth century. Sloane may have devised his own recipe for mixing chocolate with milk, though if so, he was probably not the first. (Some sources credit Daniel Peter as the inventor in 1875, using condensed milk; other sources point out that milk was added to chocolate centuries earlier in some countries.) Nonetheless, the Natural History Museum lists Sloane as the inventor of that concoction. By the 1750s, a Soho grocer named Nicholas Sanders claimed to be selling Sloane’s recipe as a medicinal elixir, perhaps making “Sir Hans Sloane’s Milk Chocolate” the first brand-name milk chocolate drink. By the nineteenth century, the Cadbury Brothers sold tins of drinking chocolate whose trade cards also invoked Sloane’s recipe.’

His collections became vast. If he didn’t collect it, he was given it, and before long he had amassed over 71,000 objects including books, manuscripts, drawings, coins and medals, and many plant specimens. Sloane asked in his will that his collection ‘[…] may remain together and not be separated and that chiefly in and about the city of London, where I have acquired most of my estates and where they may by the great confluence of people be most used.’ In keeping with that, his collections have formed the basis of three great educational institutions: the British Library, British Museum, and Natural History Museum. For the past 300 years his collections have provided invaluable information to researchers and scientists, and his plant specimens are occasionally loaned to museums around London.

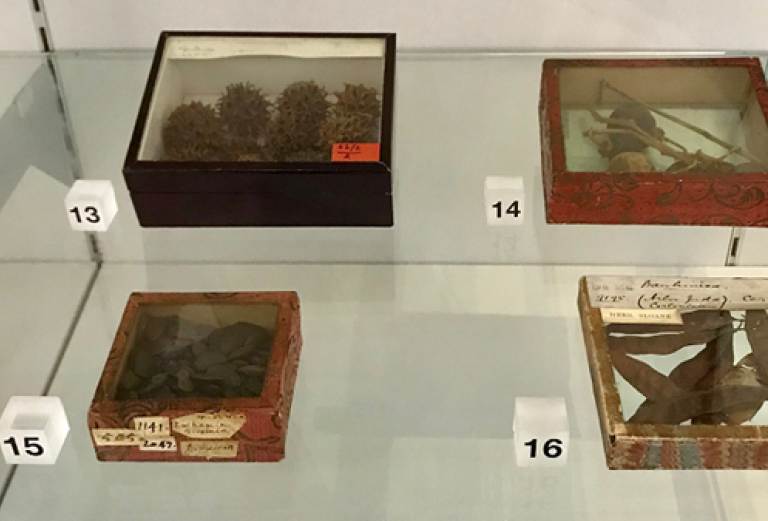

This brings us to our very own Fab Four: as of 14 January, Fulham Palace became the temporary caretaker for some of Hans Sloane’s enormous collection, whom will be with us until December 2020! I have copied their labels from the museum display:

13: Fruit of sweetgum (Liquidamber styraciflua) This tree is famous for the autumn colour and is popular in gardens. It was first recorded growing in England I 1656 at the Tradescant family garden in Lambeth. 32 years later, the natural historian John Ray saw it growing in Bishop Compton’s garden.

14: Persimmon seeds (Diospyros virginiana) Writing in 1713, James Petiver comments that “there is a large Tree of this in the Bishop of London’s Garden at Fulham”, this is probably the same tree that Leonard Plukenet, royal professor of botany and gardener to Queen Mary, depicted in his Phytographia in 1692.

15: Fruit of a wild relative of aubergine (Solanum melongena) Sloane was clearly a little mystified by these fruit, in his catalogue, he described them as “The fruit of Solanum spinosum, an pomum amoris?”, alluding to their relationship to the tomato, which at the time, was also known as ‘love apple’.

16: Eastern redbud seed pods (Cercis canadensis) This tree is one of the most beautiful in North America. It is related to the Judas tree (C. Siliquastrum) from southern Europe and western Asia. Richard Bradley, botany professor at Cambridge University, described how Bishop Compton enjoyed scattering redbud flowers on his ‘sallets’ [salads!].

My favourite part about our vegetable substances is their handcrafted wooden boxes, lovingly covered in hand-printed paper which has not faded too much during the last three centuries. You can see them in our temporary exhibition room, and access Sloane’s Herbarium with his Jamaican plant specimens via the Natural History Museum’s online database here.

Do come say hello to our new plant-astic brethren when you get a chance! The museum is open from 10:30-16:00 in the winter hours, and we look forward to showing you our newest acquisitions.

All items on loan from the Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.