Written by Alexis Haslam, Community archaeologist

As I stoically plod my way through the Fulham Palace monograph, numerous stories continue to emerge which are often surprising and, as in this case, sometimes tragic. The 17th century is an incredibly complicated period of British history with the Civil War beginning in 1642 and resulting in the execution of Charles I in 1649. This was followed by the Interregnum which ended with the return of Charles II in 1660. Fulham Palace was not impervious to the politically divided chaos of the times and it very much so has its own tale to tell.

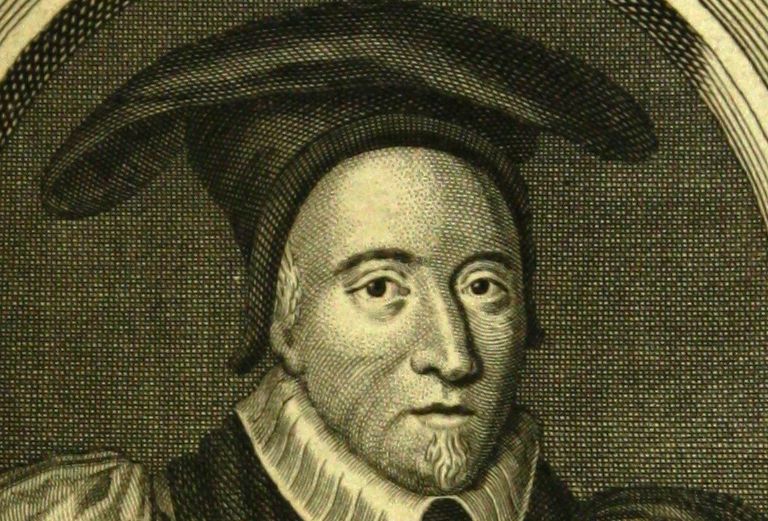

At the time the war broke out, William Juxon was Bishop of London. He had been in position since 1633 and as a close associate of both Charles I and the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, he was made Lord High Treasurer of England in 1636. With the outbreak of the war, however, prospects were not looking good for Juxon. The Root and Branch Bill, designed to abolish the role of Bishops and Archbishops and to seize their land, became law in 1642. Laud himself had been imprisoned in 1640 and was finally executed in 1645. Intriguingly Juxon managed to escape severe reprimand or punishment and was not actually deprived of the Bishopric until 1649. Viewed as a man of honesty and integrity by both Royalists and Parliamentarians he was allowed to stay undisturbed at the Palace with his secretary, Philip Warwick. He continued to be visited by ‘great persons’ and certainly met with Royalists, writing to Charles from the Palace on October 14th 1646.

Yet things were getting tough for the Parliamentarians. Cash was desperately needed to pay the Scots army who wouldn’t leave England without their wages. At this point, the decision was made to sell Episcopal land. Fulham Palace was surveyed in 1647 where Juxon was still recorded as resident, along with a Mr Haynes. Juxon seems to have remained living at the Palace until shortly after Charles’ execution. He had attended the King on the scaffold, but swiftly headed off to his family residence in Little Compton. As an aside, he appears to have taken part of the chapel with him, with this rather fabulous piece of 16th-century woodwork now residing in Steyning, West Sussex.

The Palace and associated leaseholds were purchased by an individual named Colonel Edmund Harvey for a price of £7,617 8s 10d. That’s about £1.5 million in today’s money; an absolute bargain, but this shows just how desperate Parliament was to raise cash. Harvey himself appears to have been a Citizen of London and quite possibly a silk merchant. The similarities between the Palace’s painted wall in Room 109 and the Silk Merchant’s House in Marlborough suggest that Harvey was most probably responsible for this somewhat unusual décor. In 1645 he was recorded as exporting large quantities of calves’ skins, which may indicate that he was in fact a skinner. He was a partner with the mercer, Alderman Edmund Sleigh, and a stringent Parliamentarian who had raised a London Militia Regiment of Horse in 1642. During the Battle of Newbury in September 1643 his Captain, John Juxon, was mortally wounded, dying the following month. Juxon was a direct relative of the Bishop, showing just how divided families were by the civil conflict.

Harvey was initially close to Cromwell and entertained him at the Palace, which he had made his family home. It was certainly large enough to house his 13 children! He was on the commission assembled to try the King in January 1649 but refused to sign the warrant for execution. He still remained trusted however and was appointed Collector of the Customs of London. Popular in Fulham he was able to distribute £100 to the local poor after being granted the sum by the navy following a new import duty placed on coal entering the port of London.

Things soon began to unravel for Harvey however and he fell out with Cromwell, possibly as he didn’t believe the Commonwealth’s reforms were as far-reaching as he had hoped. He was imprisoned briefly in the Tower of London in 1655, and although he returned to Parliament in 1656 he wasn’t allowed to sit in it. With the return of the monarchy in 1660, he was tried as a regicide at the Old Bailey in October where he admitted to his presence in the court that resulted in Charles I’s execution. His head was saved by the fact that he had refused to sign the warrant, although he was to spend the rest of his life imprisoned in Pendennis Castle, Cornwall, where he passed away in 1673.

Tragic as Harvey’s tale is, things took a far worse turn for his immediate offspring. His son Samuel had married Cecily (or Cecilia), the daughter of the renowned lawyer Bulstrode Whitelocke in 1658, and the couple had settled at the Palace after being granted it by Edmund. With the return of Charles II and the Bishops, serious difficulties lay ahead, however. Edmund Harvey’s guilty verdict meant that his assets and property would be seized and this of course included Fulham Palace. Juxon had been appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles II, with Gilbert Sheldon being made Bishop of London in September 1660. Bulstrode and Samuel approached Sheldon and agreed that the Palace would be returned to the See of London, yet as Cecily was pregnant they asked that the couple could stay until she gave birth; or at least that soldiers and officers would not be sent to seize the property. Sheldon agreed, yet he seems to have changed his mind fairly quickly.

On December 23rd 1660 a group of soldiers and officers forced their way into Fulham Palace, seizing the property and stealing money, plate and goods belonging to the Harvey family. Samuel was not present at the time, yet the soldiers remained for 3 to 4 days apparently swearing, drinking and dicing. With Samuel under the threat of arrest if he returned, Cecily was removed to a safe house in London. The event appears to have taken a serious toll upon Samuel who was described in Bulstrode’s diary as being ‘exceeding sad’ on New Year’s Eve. The diary then becomes somewhat vague, with Samuel being described as ‘dangerously sicke’ on the 4th of January, with Bulstrode in fear for his life on the 5th. The 8th of January record reads as follows:

‘About 6 a clocke in the morning, Whitelocke’s son Harvey dyed, his heart being broken with grief for the barbarous usage of himselfe and his wife by the Bishop of London and his Agents, and for the losse of his whole Estate, a great part of it unjustly taken from him and contrary to the Act of Generall Pardon.’

Reading between the lines it may be the case that Samuel took his own life.

Cecily moved into Whitelocke’s House on Coleman Street, yet on May 21st 1662 she was described as ‘extreame ill’ and on the 25th she was described as ‘in great daunger of death’.

The entry for the 27th of May reads as follows:

‘Between 7 and 8 a clocke in the morning, his deare daughter Cecill Harvey dyed in his house on Coleman Street, she never injoyed herself after her husbands death, whom she truly loved, as he did her, she was not much troubled att their losses, nor lesse affectionate to her husband after them, butt when he dyed, she betooke herself chiefly to her devotion… She was of a sweet disposition, and conversation, lamented by all that knew her, God was pleased upon the barbarous dealings of the Bishop of London and his Agents with her and her husband, to cast her into an illness and griefe, and shortly after to take away her childe, after that he tooke away her husband, and within 5 moneths after that (should be 15 months?), she dyed, and all their blood lyes att the doore of this Bishop.’

According to the diary Samuel and Cecily’s child was born on the 2nd of June 1661, although the notes from 1662 suggest that the baby did not survive beyond infancy.

All in all, the return of Charles II had proved the downfall of the Harvey family, with Edmund’s children subsequently reduced to the ‘greatest distress and poverty’. Although Whitelocke’s diary is written from a biased perspective, the actions of the agents and soldiers employed by Bishop Sheldon certainly seem harsh in retrospect, and the consequences of his actions in regards of Samuel and Cecily had the most tragic consequences.