Written by Siân Harrington and Dr Celia Mill.

This blog outlines the active research being undertaken at Fulham Palace into the involvement of the Bishops of London in colonialism and transatlantic slavery. It includes highlights of a visit to Virginia, USA, in May 2025, and research undertaken in July 2025 by Dr Celia Mill into the fate of the enslaved people mentioned in the wills of the Porteus family (in relation to Bishop Porteus, a late 18th century Bishop of London).

Background

In 2022, Dr Celia Mill uncovered evidence that Bishop Beilby Porteus (Bishop of London 1787 to 1809 and historically cited as a leading British abolitionist) inherited his family’s estate in Virginia, becoming an absentee plantation owner and enslaver.

Beilby Porteus’s grandfather, Edward Porteus, landed in Virginia from England in 1675 and from at least 1680 owned 500 acres of tobacco land in Virginia [1], in addition to a small plot of land in Gloucester Town. The Porteus family used enslaved African labour to grow this labour-intensive and extremely lucrative export crop. Edward also played a role in the trafficking of enslaved Africans. His main role was probably as an agent, either for the Royal African Company, or directly for the London merchant Jeffrey Jeffreys.

In addition to the land in Virginia, Beilby Porteus was later in life also the beneficiary of family-owned land in Port Tobacco, Maryland.

The Porteus family’s ownership of enslaved people

The will of Edward Porteus (Beilby’s grandfather), dated 1693/4 left his wife ‘his horse Jack with her saddle and furniture; also her clothing and his largest silver tankard and caudle cup, a featherbed and furniture, the time his English servant maid Betty has to serve’ and an enslaved African girl called Cumbo.

Bishop Porteus’s father, Robert Porteus (1679 – 1758) inherited his father’s 500 acres in Virginia. Robert married twice, having 19 children altogether, and moving to England with his second wife some time before Beilby was born in 1731.

Like Edward, Robert also mentions an enslaved African in his will, but in his case uses it to say that the ‘honest old man’ called Peter should be freed from slavery and given ‘comfortable maintenance … for one in his station’. This includes a ‘coat Waistcoat and Breaches Two canvas shirts Two pair of yarn stockings and Two pair of shoes be provided for him and given to him in every year so long as he lives’.

Robert also stipulates in his will that he wants his sons Edward (d. 1794) and Beilby to be his executors, that they should share the remaining third of the surplus between themselves and the children of his dead son (also called Robert), and to direct the management or sell his estates as they see fit.

Further research

In 2023, Fulham Palace Trust teamed up with Kent University to discuss the creation of a PhD opportunity to undertake more research into the Bishop of London’s role in the early period of colonisation in North America. A funding bid to the Consortium for the Humanities and the Arts South-east England (CHASE) was successful, and in September 2023 Eleanor Hex began her research as the successful candidate, looking at the Bishops of London and their Workforces in the Tobacco Colonies, c.1680-1800. Eleanor was able to make a five-week study trip to Virginia, USA, in April/May 2025 to undertake further research.

Visit to Virginia, May 2025

Siân Harrington, CEO of Fulham Palace Trust is one of Eleanor’s supervisors on her PhD, and was able to visit Virginia from 15 – 20 May 2025 to catch up with Eleanor. Siân shares more about her and Eleanor’s detective work to find the site of Bishop Porteus’s tobacco plantation in Gloucester County, Virginia.

Eleanor and I had a great day trip on 16 May 2025 courtesy of the museum team in Gloucester County, volunteer Bill Lawrence and museum specialist Sidney Ripley. Sidney and Bill gave us a fascinating tour around the Gloucester Museum of History and took us out to Fairfield Plantation, a former tobacco plantation being excavated by the Fairfield Foundation, and the remains of Rosewell House, formerly once one of the most elaborate homes in the American colonies.

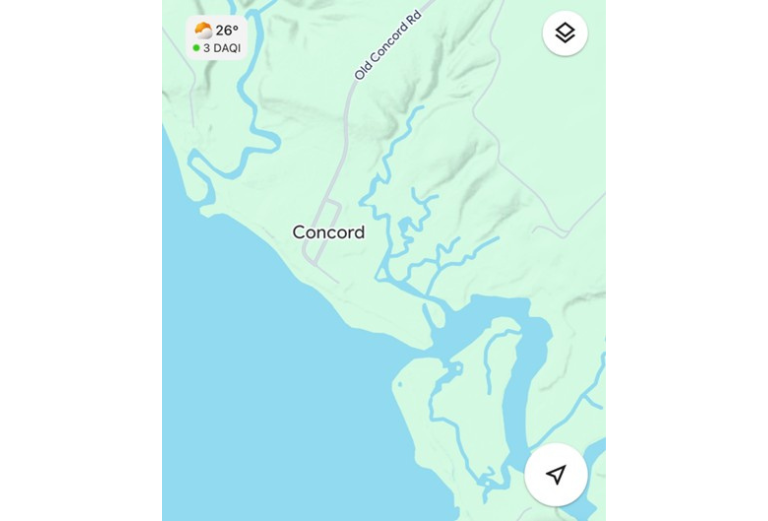

Our trip to find the land owned by the Porteus family began from the main road leading out of Gloucester Town and took us cross country towards a small settlement called Concord, on a loop of road (Old Concord Road turning into Old Concord Lane) right on the banks of the York River between Jones Creek and Sandy Creek.

While Concord is a name dating back to a tobacco plantation that existed there in the 17th & 18th centuries, there is no trace of the Newbottle house or tobacco plantation which was adjacent to Concord and owned by Edward Porteus, grandfather to Beilby Porteus. A newspaper article from 1964 tried to pinpoint the site of the house, and the general consensus was it was to the north of the Concord site, an area which is now quite overgrown. We were not able to spot the large pine tree that was photographed in 1964 and is supposed to indicate the location of the Newbottle house. I was told by Bill Lawrence that he tried to speak to an older gentleman who might be able to place the location of the house, but he was ill in hospital.

Do we know any more about the people whom the Porteus family enslaved?

Dr Celia Mill talks here about her further efforts to trace the enslaved people mentioned in the wills of the Porteus family.

I have not been able to find any inventory or distribution records for Edward’s wife, Robert’s wife, nor Edmund’s wife Martha and so do not know whether any of their property was sold before being passed down according to their husbands’ wills. A search for the enslaver name Porteus in the database: All U.S., Virginia Untold: Bills of Sales and Deeds of Enslaved Individuals, 1703-1865 does not reveal any further relevant results [2].

As a result, it has not been possible to trace Peter, the ‘honest old man’ mentioned in Robert Porteus’ will, nor the servant Betty, nor the enslaved girl called Cumbo mentioned in his father Edward’s will of 1693/4. However, the name Cumbo often appears in inventories and sale lists in Virginia and there are instances where the dates and locations could very possibly refer to the Cumbo enslaved by the Porteus family. This is completely speculative, and there is no clear proof that this is the case.

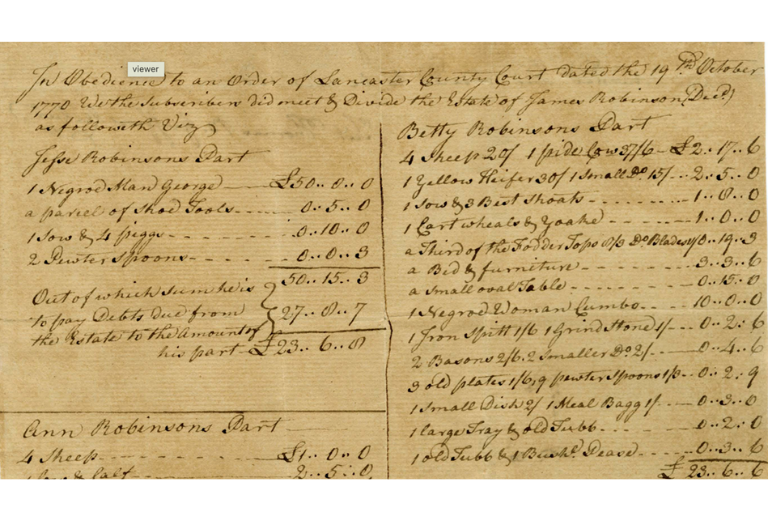

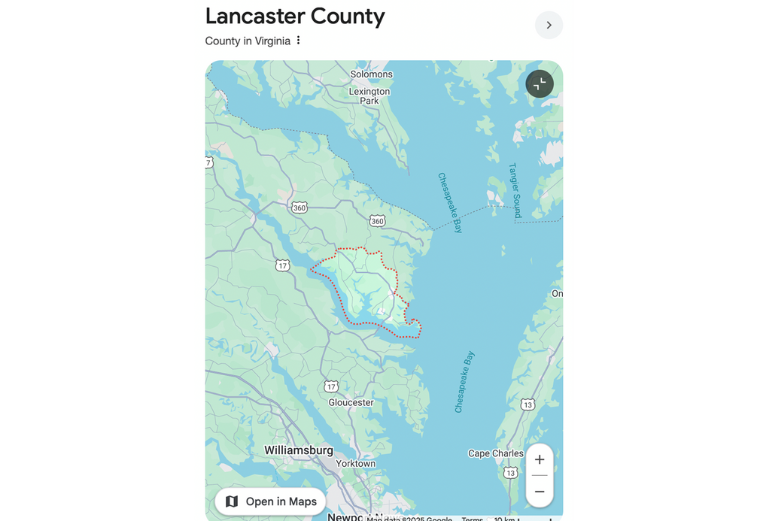

The first example in the records is in a 1764 inventory of a James Robinson’s estate in Lancaster County, Virginia, about fifty miles from Gloucester County. Edward has a possible link here as he seems to have moved to Gloucester from Lancaster. It may therefore be that his family retained social and business links with the area [3].

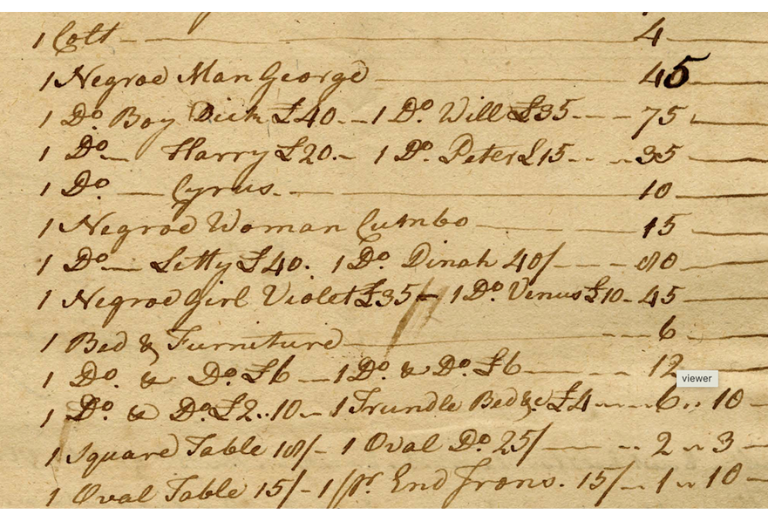

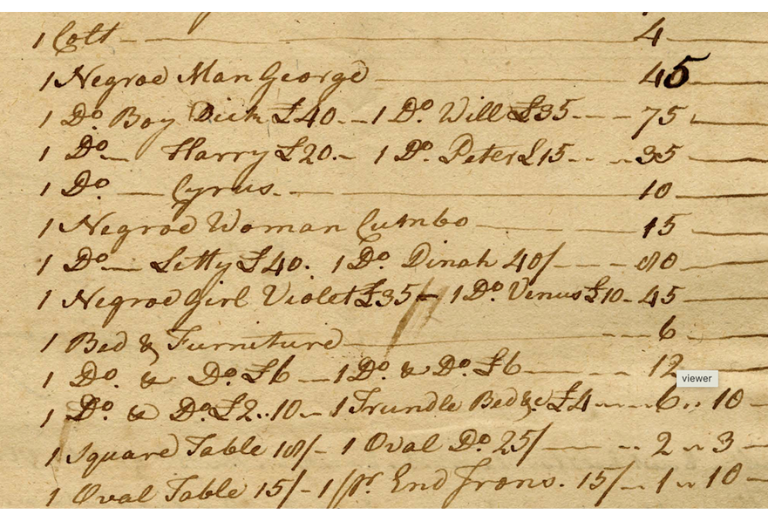

In Robinson’s inventory, a woman called Cumbo is listed along with other enslaved people and amongst household goods such as furniture, livestock, etc. It is conceivable that this is the same Cumbo, now in her seventies, that Robert referred to, especially as the value given against her name is only £15 compared to £35 for a girl called Violet and £40 for a woman called Letty [4].

Six years later, in 1770, James Robinson’s estate is shown divided up amongst various beneficiaries. An enslaved woman called Cumbo is listed under the property allotted to Betty Robinson Dart, and this time Cumbo is given a value of £10, possibly commensurate with her increase in age [5].

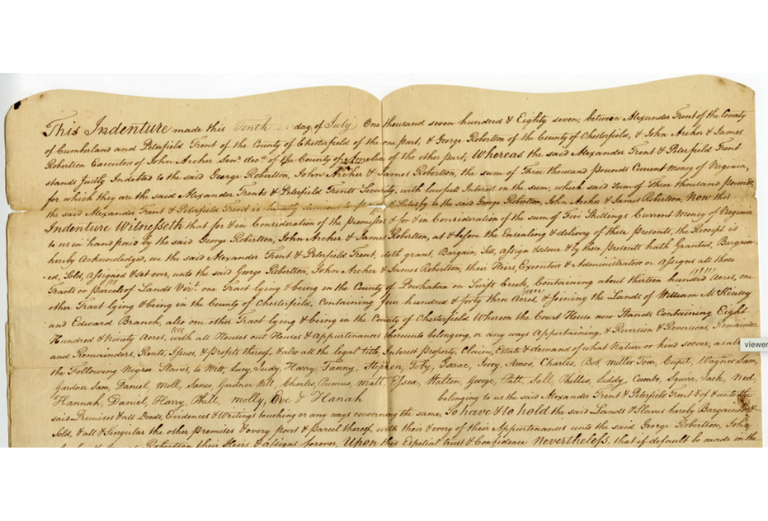

Less likely, but just about possible, is that Cumbo is in a list of enslaved people’s names written in a 1788 indenture [6].

This transfers land and property between a George Robertson and Alexander Trent in Chesterfield County, Virginia, about seventy miles from Gloucester. I think this possibility less likely as it would put Cumbo in her eighties but no indication is given of her age.

So, Cumbo’s story might be that after she was bequeathed to Edward Porteus’ wife in his will, she was at some point sold to James Robinson and then, as an old woman, given by him to Betty Robinson Dart. In this telling, Cumbo lived a long life in the Gloucester and Lancaster counties of Virginia, possibly serving the women of the house. She does not appear to have been given her freedom at any point.

Please note that in the excerpts of documents below there is some difficult language used, and that enslaved people are listed along with other property, such as furniture.

Sources cited

[1] David Dobson, Scots on the Chesapeake, 1607-1830. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1992, p. 125. https://archive.org/details/scotsonchesapeak0000dobs/page/124/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater&q=porteous;

The Vestry book shows that Edward Porteus was active in Petsworth Parish from at least 14th October 1680 when he is mentioned in a Vestry meeting. The Vestry book of Petsworth Parish, Gloucester County, Virginia, 1677 – 1793. Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1979, p. 16. https://archive.org/details/vestrybookofpets0000pets/page/64/mode/2up?q=edward+porteus

[2] Virginia Untold: Bills of Sales and Deeds of Enslaved Individuals, 1703-1865. Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. Accessed via ancestry.com

[3] Dr and Mrs William Carer Stubbs, Descendants of Mordecai Cooke of Mordecai’s Mount Gloucester Co. VA. 1650 and Thomas Booth of Ware Neck Gloucester Co. Va. 1685 (New Orleans, 2nd ed. 1923, first edition 1896), chapter: The Cooke Family of Gloucester County, Virginia, p.14. Accessed via ancestry.com

[4] Robinson, James: Fiduciary Record, 1764, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. Accessed via ancestry.com

[5] Robinson, James: Fiduciary Record, 1770, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. Accessed via ancestry.com

[6] Source: Lucy, etc.: Deed, 1788, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. Accessed via ancestry.com