Written by Dr Celia Mill, archive research project manager.

It has long been known that Bishop Beilby Porteus’s father owned a plantation in Virginia before moving the family to England and continuing to profit from the estate as an absentee landlord.

My research has shown that Beilby’s grandfather, Edward Porteus (d. c. 1700), a ‘gentleman’ owner of ‘Newbottle’, an estate in Scotland, moved to Gloucester Town, Virginia, where he bought 500 acres of tobacco land and served as vestryman and churchwarden. He owned a moderate sized plot in Gloucester Town itself measuring 16.5 ft by 132 ft, with most of the other men owning at least two plots, and one as many as six. Nevertheless, Edward Porteus was an elite plantation owner and member of the community.

Through trading arrangements between the Royal African Company and the London tobacco importers, in Virginia, unlike the West Indies, only the elite planters had access to enslaved African labour. By the 1690s, their workforce was nearly all made up of enslaved Africans, whereas up to forty percent of workers for ordinary planters by the end of the century were still white servants.

Edward Porteus played a role in the trafficking of enslaved Africans. In 1685 and 1686, Captain Marmaduke Goodhand of the Speedwell is ordered to sail to James Island (now Kunta Kinteh Island in the Gambia river, Africa), and collect 200 enslaved Africans. He was instructed to take them to Maryland and Virginia respectively. Edward was listed as one of the men to whom they should be delivered and was therefore clearly well placed to buy trafficked Africans to work his own land.

Edward’s main role, however, was probably as an agent, either for the Royal African Company (who owned the ship), or directly for the London merchant Jeffrey Jeffreys. Jeffreys paid for the “freight and care” of the enslaved and is mentioned in Edward’s will. Other elite plantation owners would have had the opportunity to buy their own enslaved workers from each shipment received by Porteus and his fellow planters. According to Dr Nick Radburn (co-editor of slavevoyages.org), each colonist usually acquired only small numbers of enslaved people from the ships at this time.

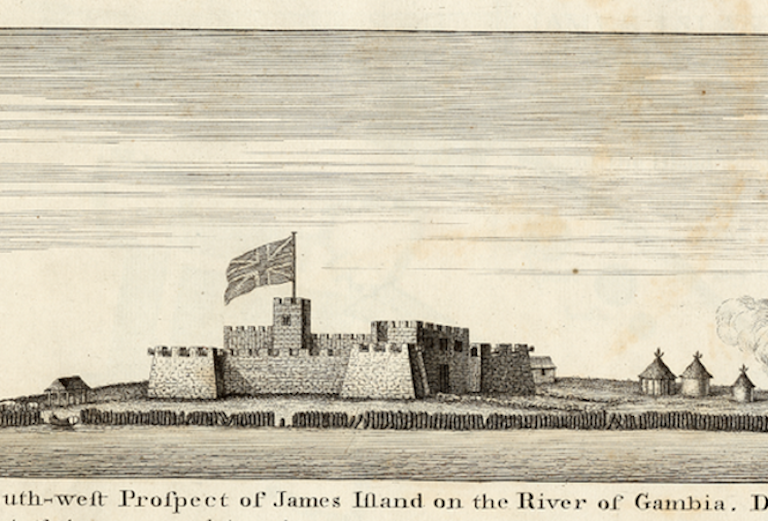

The Royal African Company owned a fort on James Island where they imprisoned enslaved Africans before they were transported by ship. Once in Virginia, the enslaved people were forced to produce tobacco. This entailed long, back-breaking hours of ploughing vast acres of sometimes hard-baked land, sowing seeds, tilling the earth and checking for caterpillars. Any holes in the leaves would make them unsellable, so every egg had to be taken off. After picking, the leaves were dried, packed in barrels, and transported on ships to England. A more detailed account of eighteenth-century tobacco growing can be found on the Colonial Williamsburg website.

Edward’s will of 1693/4 stipulates that a third of his estate should be left to his wife and the rest to his son and executor Robert Porteus. He also left his wife “his horse Jack with her saddle and furniture; also her clothing and his largest silver tankard and caudle cup, a featherbed and furniture, the time his English servant maid Betty has to serve” and an enslaved African girl called Cumbo.

It also appears that Edward might have had both white servants and enslaved Africans working his tobacco fields, as his will requests that both be ‘kept on his plantations’, with the produce to be sent every year to England.

Bishop Porteus’ father, Robert Porteus (1679 – 1758):

Robert inherited his father’s 500 acres in Virginia and the estate in Scotland but was also the recipient of a further 692 acres in Petso Parish, 542 acres of which was ‘granted to Robert Lee in 1662 and by several conveyances now to Porteus’ in 1704. There is some speculation that Robert Porteus’ mother’s first marriage was to Robert Lee and that Porteus indirectly inherited the land through her.

Like his father, Robert Porteus was active in the parish as church warden, providing window casements for the church in exchange for 300 pounds of tobacco, which was the currency at the time.

Robert married twice, having nineteen children altogether, and moving to England with his second wife some time before Beilby was born in 1731. Robert seems to have left some grown up children in America, including Edmund Porteus who owned a plantation in Port Tobacco, Maryland.

Like Edward, Robert also mentions an enslaved African in his will, but in his case uses it to say that the ‘honest old man’ called Peter should be freed from slavery and given ‘comfortable maintenance … for one in his station’. This includes a ‘coat Waistcoat and Breaches Two canvas shirts Two pair of yarn stockings and Two pair of shoes be provided for him and given to him in every year so long as he lives’.

Robert also stipulates in his will that he wants his sons Edward (d. 1794) and Beilby to be his executors, that they should share the remaining third of the surplus between themselves and the children of his dead son (also called Robert), and to direct the management or sell his estates as they see fit.

Bishop Beilby Porteus (1731 – 1809):

At the age of 27, Beilby Porteus, together with his brother Edward, inherited their father’s estate in Virginia, becoming absentee plantation owners and enslavers before they sold it.

In 1759 the land was valued at around £600 (around £130,000 today), which was a comparatively low amount. The tenants who were farming the land at the time would have been “glad to throw up their lease” as they were making yearly losses of at least £30.

The enslaved workers and the ‘stock’ were considered to be slightly more valuable, at £1200 (about £260,000 today). But that was only if they were sold in the next three or four years, since the value of enslaved people currently living in Virginia would decrease if the number of people trafficked there increased.

Towards the end of his life, Beilby was also the potential beneficiary of land in Port Tobacco, Maryland. His much older brother Edmund, left his plantation of about two hundred and fifty acres to his widow, Martha, for her life, and then to Beilby. Beilby in turn willed his interest to his great-nephew, Thomas Porteus. In 1759 the land was valued at only £50 (about £12,000 today) and it was noted that Martha was still alive. It appears that this was still the case in 1790, when a census lists her as living with nine enslaved Africans, and it might even be that she outlived Porteus himself, with the proceeds going directly to his nephew.

There is much we still don’t know about the Porteus family in North America and the people whom they enslaved. A combination of records having been destroyed in fires and as the result of the Civil War, and a lack of detail ever written about the lives of enslaved people, makes the research difficult, but we are still looking to see what more we can find out.