Alexis Haslam, community archaeologist

As an archaeologist working from home, I’ve found the Palace and its history weaving its way through my life. So when asked about the history of the moat, it seemed like the perfect time for a bedtime story. Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

Once upon a time the River Thames was very wide, much wider than it is today. There were no embankments or river walls meaning that it was relatively fast flowing, but broader and shallower than it is now. As the river meandered its way along, it existed as what we call a ‘braided river system’, with streams and rivulets criss-crossing all over the place. A bit like this…

So, as you can see there were probably lots of little islands or ‘eyots’, some of which still exist today – like at Isleworth, Brentford and Chiswick. Our site at Fulham Palace was a rather large one of these, making it a popular spot in the Late Mesolithic to Early Neolithic and again in the Roman period.

The water channels forming the eyot ran down Bishop’s Avenue and along Fulham Palace Road and Fulham High Street, discharging into the main river at, or around about, Putney Bridge. There is a theory that a spring also fed this channel somewhere near Colehill Lane.

The stretch along Fulham High Road was actually known as the Fulham Stream, and this was only filled in during the 18th century. In fact, even then it was replaced by a large culvert (drain), meaning that water still flowed down it until fairly recently. The section of the moat that we call the ‘churchyard stretch’ was excavated in the medieval period, separating the Palace grounds from All Saints church for the first time (I have theorised this might have been done by the Vikings, but it really is just a theory). The riverside stretch of the moat was probably dug at or around about the same time. In essence, two sides of our moat are canalised natural water systems, with the other two sides dug in the medieval period. The idea of it being a 100% man-made moat are totally farfetched. Its waaaaaay too big.

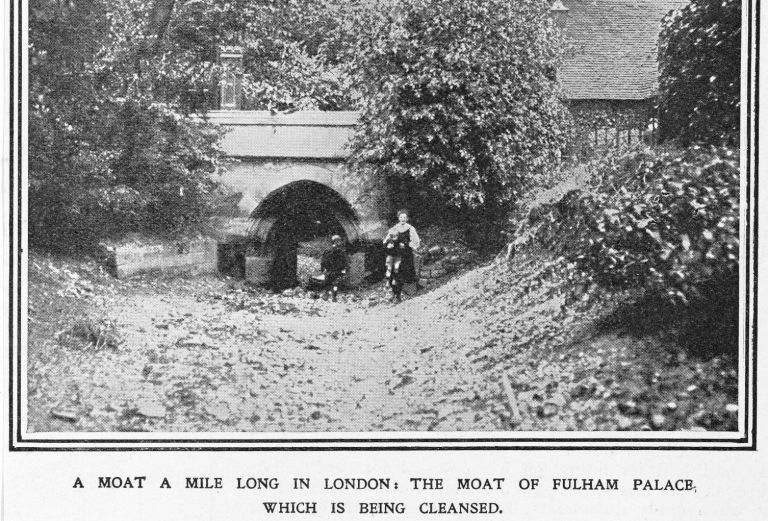

Our earliest reference to it is as an ‘earthwork’ is in 1163-80 and it is referred to as the ‘magna fossa’ or great ditch in 1392. That’s just in terms of historical reference though. It was clearly here way before that. It was certainly still here in 1485 and was only filled in during the early 1920s when Bishop Winnington-Ingram got sick of paying for it to be dredged out. The incidences of drowning children were also somewhat bad for press.

So there you have it. Without going into the complexities of rising and falling water levels during the periods between the Late Mesolithic and modern times (which would have resulted in you going straight to sleep), a brief synopsis of the Fulham Palace moat. A natural channel which was canalised and altered by those Bishops in the early(ish) medieval period. That raises a whole bunch of other questions about the separation of the Manor from the Parish Church, but I’ll save that for another evening.

Goodnight readers! (and yes, this home working is sending me completely over the edge!)