Bishops of London and the Church of England

Discover more about some of the key Bishops of London by selecting the names below.

John King, Bishop of London 1611 - 1621

John King was a member of the Virginia Company which founded James Town, Virginia, in 1607.

In 1617 he hosted a dinner in London with tobacco farmer John Rolfe and his wife Pocahontas (who had been baptised with the name Rebecca) as the main guests. The dinner was intended to raise interest in and money for the Virginia Company and James Town and to fund booklets of sermons and ballads promoting the colonisation of Virginia. The company was keen to emphasise to the public that the emigration of English Christians to Virginia, with the aim to convert the Native Americans there, was in the country’s best interests.

In 1620 Bishop King was still raising money, along with other Church of England dioceses around the country. He gave a sermon on charity in which he tells his audience that: ‘Charitie beginneth at hir owne house’, celebrating the fact that the Diocese of London had raised £1,000 to support the Virginian church:

“Your Colonie in Virginia (I named hir the little sister that had no breasts) hath drawne from the breasts of this Citty and Dioecesse a thousand pounds towards hir Church.”

The Virginian council also asked Bishop King for help in getting ‘pious, learned, and painful ministers’ but he never had any official ecclesiastical jurisdiction there or in any other colony.

William Juxon, Bishop of London 1633 - 1646

Bishop Juxon was Bishop of London from 1633 until the ‘interregnum’ in 1646. Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Juxon became Archbishop of Canterbury, a position he held until his death in 1633.

The coat of arms of Bishop/Archbishop Juxon was granted to the Juxon family in 1630 and features four African heads. Research into the Juxon coat of arms was undertaken by Kent University in 2022 as part of a project entitled ‘Figuring Juxon’s Arms: Power, Place and Empire’. A number of ideas have been put forward by Kent University and its partners to explain the use of the African heads on the coat of arms, and Fulham Palace Trust has also undertaken its own research.

Family links

Juxon family members had their own personal connections to the early trade in sugar, trading cloth for sugar within Europe/Africa. Later there were connections with Virginia and the Caribbean.

The Juxon family were very involved with the Merchant Taylors – Both Bishop Juxon and his brother Thomas Juxon went to the Merchant Taylors School. The Bishop’s cousin, John, was a Citizen of London free of the Merchant Taylors and he was a sugar baker / refiner. In 1619 he bought the Manor of East Sheen and Westhall.

In 1585 Queen Elizabeth I established the Barbary Company and an agreement with Morocco meant English ships could pass safely through Ottoman seas and ports. This gave trading privileges to the English, especially for sugar – at this point most sugar was coming from North Africa and notably Morocco.

Camels first appear on the Merchant Taylors heraldic symbol in 1586 which is clearly a reference to eastern trade. English cloth was traded for Moroccan sugar. Do the African heads on the Juxon shield represent Moroccans?

The African heads on the coat of arms might also represent an involvement of the Juxon family in the re-taking of Spain and Portugal from Muslim rulers (the Iberian Crusades of the 8th century up to 1492).

There are later links with the Juxons in the Caribbean and Virginia. Bishop Juxon’s cousin Thomas Juxon left money in his will for his son William, who was in Barbados at the time, following a period in Virginia. As William had mental health problems, Thomas was entrusted with the money. There are also Jacksons in Jamaica who claim to have been related to the Juxon family and Bishop Juxon.

The Bishop’s other nephew John acquired 400 acres and a brick house in the area between Queen’s Creek and Carter’s Creek in Virginia. His mother had inherited it as a result of a debt from the landowner Robert Spring. In 1685 John sold the land to Reverend Rowland Jones (the great-grandfather of Martha Washington). When he died he left the land to his children – the land is recorded as plantations and Revd Jones left 6,000lbs of tobacco to his daughter.

Divine nobility?

The official description of Juxon’s heraldic arms is:

“Or, a cross Gules between four blackamoors’ heads affrontee, couped at the shoulders, proper, wreathed about the temples Gules.”

A translation of this might read:

“Gold colour background, a red cross between four Blacks’/Moors’ heads facing the viewer, cut off at the shoulders, in their natural colour, wearing red circlets around their heads.”

The colour of the cropped African heads is described as ‘proper’ – this indicates a natural colour readily understood by artists or designers of the time.

Although there is the suggestion that the African heads represent the Juxon family’s links with slavery, it is also possible that the heads represent nobility and courage (traits the Juxon family presumably aspired to), at a time when the African continent and Blackness were not necessarily viewed negatively in Europe. This is something that Dr Onyeka Nubia* of Nottingham University talks about in a blog for Kent University as part of the above project.

For further information about William Juxon and his time as Bishop of London, see this article by Alexis Haslam, Fulham Palace community archaeologist.

*Dr Onyeka Nubia is a leading historian on the status and origins of Africans in pre-colonial England from antiquity to 1603.

Thanks to Professor Kenneth Fincham and Dr Ben Marsh at Kent University.

For further information about William Juxon and his time as Bishop of London, see this article by Alexis Haslam, Fulham Palace community archaeologist.

Henry Compton, Bishop of London 1675 – 1713

Henry Compton’s grandfather, William, Lord Compton, Baron of Compton (d. 1630), appears to have funded early colonising expeditions. An instruction book for evaluating land in ‘the plantation of Ireland or Virginia’, published in 1610, was dedicated to him. A later history also lists ‘William, Lord Compton, now Earle of North-hampton’ as one of the Adventurers for Virginia. Bishop Compton therefore clearly had historical family money invested in Virginia, but it is not known the extent to which he benefited from this personally.

Henry Compton (1632-1713) was the youngest son of the Royalist Earl of Northampton who was killed at the Battle of Hopton Heath in 1643. He went to Queen’s College, Oxford, followed by travel abroad from 1652 to the Restoration in 1660 when he joined the Horse Guards. He later went to Cambridge and took holy orders. In 1674 he was made Bishop of Oxford and by 1675 he had risen to be Dean of the Chapel Royal and Bishop of London.

In September 1686 King James II suspended Compton as Bishop of London for not disciplining Dr John Sharpe, the future Archbishop of York, for preaching against Catholicism.

By the time Compton became Bishop of London, the Church of England had been in America for nearly 100 years, but they had not put any clear ecclesiastical or doctrinal structures in place. This changed after the Protestant William III and Mary II ousted the Catholic King James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1688/9 with Compton’s support. The Archbishop of Canterbury would normally preside over the monarch’s coronation, but he refused to do so for William and Mary. As a result, Compton took the Archbishop’s place and continued to influence the monarchs with his own ecclesiastical agenda.

Before Bishop Compton, there had been no episcopate in the colonies at all. He was the first to appoint commissaries to act as his representatives there. The office of the commissary was entrusted to a senior clergyman. His main function was to act as episcopal delegate, keep his bishop informed of the state of the church, behaviour of the local clergy, political situation, etc. In 1676 Compton granted his first licence to Paul Williams to preach in America and afterwards to other clergymen and schoolmasters to America and the West Indies.

One of his commissaries was James Blair who remained in post for 54 years. He was a key founder of William and Mary College in Virginia and Bishop Henry Compton was made its first chancellor.

Another commissary was Thomas Bray who in 1695/6 who set up the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), and in 1699 secured its sanction for his scheme of promoting Religion in the Plantations. He lobbied London on Maryland’s behalf, securing ‘the colony’s fragile Anglican legal establishment’ in the face of Quaker opposition. Bray created special ‘Bray Libraries’, wooden cabinets filled with books he thought necessary for clergymen to have as part of their pastoral administration. They were sent to America as well as throughout England. One cabinet, still partially filled with the original books, is at Canterbury Cathedral Library. The ‘Friends of Dr Bray’ founded a school for free and enslaved Black children in 1760 in Williamsburg, Virginia.

It appears however, that Compton did not automatically have jurisdiction over every colony. Minutes for the Committee of Trade and Plantations records of 1685 record that the Bishop of London asked specifically for: jurisdiction of the West Indies except for marriage licences; will probates and disposal of parishes; that schoolmasters there needed a licence from himself; and that a St Andrews Parish should be established in Jamaica. The record states that the committee would discuss it further when the Bishop was present. There is no record of this next meeting, but Compton appears to have been successful as he sent William Walker to be commissary there in 1690.

In 1701, the SPCK was reconstituted by Compton as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG). This missionary society was granted a royal charter by King William, and each Archbishop of Canterbury became its president. The SPG was therefore clearly associated with the British royal and Anglican establishment. It financed ministers working abroad and required yearly reports which Compton, as SPG board member and the ministers’ prelate, had access to. It was the SPG to whom Christopher Codrington bequeathed his plantations on Barbados, because of their remit to teach the Christian message in the colonies.

Bishop Compton’s interest in plants and botany meant that he often asked ministers to send him specimens from abroad. One of these was Reverend John Banister who was also a trained botanist. Banister sent many specimens back to Fulham Palace, collected we assume with the help of Native Americans and enslaved Africans. Early in his time there, he wrote asking a colleague to persuade the Royal African Company (RAC) to send him four or five young enslaved Africans to help him make a ‘pretty livelihood’. It is not known whether the RAC responded, but Banister later went on to import enslaved Africans to work his plantation in Bristol Parish, Charles City County, Virginia. He became well respected within Virginian society and was a co-founder of the William and Mary College. He was accidentally shot while out collecting plants in 1692.

Compton also had links with naturalist, apothecary and Fellow of the Royal Society, James Petiver, who used ships’ surgeons and captains on board ships transporting captured Africans to transport plants and seeds. These men were often working for the South Sea Company who traded in enslaved Africans.

Morgan Godwyn, c. 1640 - 1687

As the monarchy was at the heart of the English trade in enslaved Africans, any protestations against that trade could be seen as direct opposition to the King himself and therefore sedition. The Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of London were closely allied to the Crown, sitting on the Board of Trade and Plantations, the Privy Council and other government committees. Any misgivings they might have had are difficult to detect in the historical record.

There were, however, some late 17th century dissenters within the Church of England, the chief of whom was Morgan Godwyn (baptised 1640 – d. 1687). Godwyn had been a minister in Virginia and Barbados, seeing at first hand how the planters and enslavers lived, what they deemed important, and how badly they treated the enslaved Africans working on their estates. He was concerned that no attempt was made to convert enslaved Africans and appalled that trade and money, or mammon, was prized above God.

Between 1681 and 1685 he wrote and published his thoughts on the subject. In some parts he gets close to saying that slavery is against God, while in others he acknowledges that it can sit within Christianity if society is governed and ordered correctly. It could be that he was trying to appease the planters, and using a standard humility conventions towards the King in an attempt to mask his more forceful objections. Author and academic Holly Brewer has argued that this could be the case, particularly in the light of Godwyn’s last publication, a sermon which he read in Westminster Abbey shortly before King James II’s coronation in 1685:

“Trade preferr’d before religion, and Christ made to give place to Mammon: represented in a sermon relating to the plantations.”

Brewer’s view is that Godwyn could have been seen as publicly criticising James personally, especially given that James continued as governor of the Royal African Company after becoming monarch, a position he held from 1660. Further to this, the publication of this sermon is the last time Godwyn appears in the public record. Brewer has been unable to find any details of where Godwyn was held, only his burial record of 1687. She has however discovered that Godwyn’s mentors were investigated for sedition and that many others were detained without trial between 1685 and 1687 by the official censor Roger L’Estrange. There was one death during this time.

Brewer speculates that Godwyn was imprisoned by the Crown, without trial and never released, for publicly denouncing the actions of the monarch.

So while the Church was undoubtedly bound up with slavery from the beginning, there were some early dissenting voices, and the Church of England could theoretically have chosen to take a different line. Author Travis Glasson argues that early texts written by Morgan Godwyn, George Keith, and Anthony Hill all agreed that, “the Bible provided the best way to understand how Christians could conceptualize and practice slaveholding” but differed in their nuance and emphasis.

Glasson’s view is that texts like these show that when the SPG was formed in 1701 it, and by extension the Archbishop of Canterbury who chaired the Society, could have gone in several different directions and that, “Anglican responses to slavery were not predetermined or unanimous” at that time. That may be so, but high ranking clergy would have been well aware of the political expediency of reinforcing, rather than questioning, the wishes of the monarch.

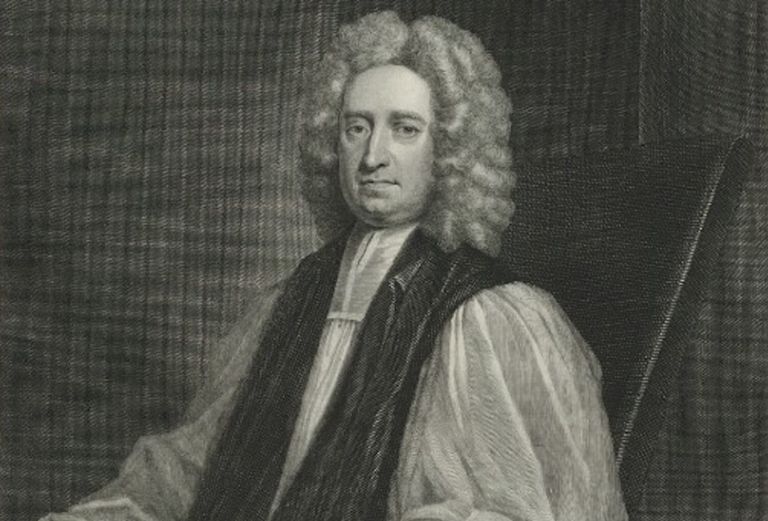

John Robinson, Bishop of London 1713-23

John Robinson (b.1650-d.1723) was a diplomat for nearly 30 years before returning to Britain in 1709, and was largely based in Stockholm in Sweden.

On his return to Britain, Robinson was appointed Dean of Windsor and of Wolverhampton. In 1713, as Bishop of Bristol and Lord Privy Seal, Robinson negotiated and signed the Treaty of Utrecht, ending the War of Spanish Succession.

The treaty also granted a 30 year monopoly – the Assiento – for British ships under the aegis of the South Sea Company to transport enslaved Africans to the Spanish ‘colonies’ in the Americas, including the Caribbean, where they worked the mines and tobacco and sugar farms.

The monarchs Louis XIV of France, his grandson Philip V of Spain and the British Queen Anne signed the treaty.

Unlike King William before her, Queen Anne thoroughly approved of the trade in enslaved Africans. She wanted to gain for England a larger share in the international slave trade and fought to gain the Assiento from France during negotiations over the Treaty of Utrecht in 1712.

As a consequence of the treaty and Charles II’s earlier acquisition of the forts on the African coast, England transported more than half of the enslaved Africans sent to all of the New World by mid-century.

As soon as he became Bishop of London, Robinson sat on the Barbados committee, a part of the Society for the Propagation for the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), which sent missionaries to the British ‘colonies’ to convert people to Christianity.

Bishop Robinson recommissioned Bishop Compton’s commissaries and sent new ones to Maryland, South Carolina, Barbados, Jamaica, and Leeward Islands between 1716 and 1719.

Robinson died in Hampstead and is buried at All Saints Church, Fulham.

Edmund Gibson, Bishop of London 1723 - 1748

By the time Edmund Gibson became Bishop of London, it had become unclear where the Bishop of London’s ecclesiastical authority overseas came from. Instead of continuing the habitual practice of re-appointing commissaries as Compton and Robinson had done, Gibson did not recommission any representative for his first five years as Bishop of London. He investigated the legality of the situation, finding that the plantations were under the aegis of the monarch rather than a diocese, bishop, or Archbishop of Canterbury.

A report written around 1725 called ‘The Case of the Bishop of London’s Jurisdiction in the Plantation’ starts by saying his jurisdiction has “been long understood and taken for granted … by an Order of Council in the reign of King Charles the second” but goes on to say that no such order has been found. From letters written by Bishop Compton to the governors of Virginia and Jamaica, Gibson’s investigators did find evidence that an order had been made. But the report concludes that because there has been so much confusion between the commissaries and the Governors over who has the power to do what, Bishop Gibson will not appoint any more commissaries “in any one of the Governments, till his majesty’s pleasure may be known, and till the Extent of this jurisdiction shall be explained and ascertained”.

By not reappointing any commissaries for five years, however, the hostility of the planters and colonial authorities, and their resistance to religious authority, became entrenched.

The report notes that by 1721 the Bishop of London’s jurisdiction had already “become merely nominal”. Much of the commissary’s duties were transferred to Governors who were particularly keen to keep the authority for appointing clergymen to their benefices, granting marriage licenses, and dealing with the probate of wills, all of which incurred fees. Commissaries were already prohibited from “inflicting the least censure of any kind for the greatest immorality either of laity or clergy”.

The planters often did not want their enslaved workforce to be converted to Christianity or to be taught to read. They were also worried that allowing large groups of people from different plantations to meet every week would lead to planned uprisings. There were also concerns that conversion to Christianity through baptism would mean that enslaved people would become free and several laws were passed across the colonies to make sure this was not the case.

In 1727, Gibson published two letters to the clergy, planters, and governors, asking them to teach the Christian message to enslaved people. He received a hostile reply from enslavers worried that enslaved people would think they were free if baptised, which would disrupt the “nation’s trade to Guinea and the sugar colonies”.

This seems to have been borne out in 1731 when an uprising in Chesapeake, Virginia was linked to the idea that Christians could not be enslaved. The reinstated commissary James Blair wrote to Bishop Gibson explaining that he thought the uprising was linked to a belief that baptism could lead to manumission and that most of the enslaved did not take Christianity seriously but

“only are in hopes that they shall meet with so much the more respect, and that some time or other Christianity will help them to their freedom”.

Despite these setbacks, Bishop Gibson did try to advocate for the conversion of the enslaved. When he first became Bishop of London in 1723, he sent a questionnaire to all Anglican clergy in the colonies asking what the situation was like in their area, including how many enslaved people they had baptised. Throughout the 1720s and 1730s he was a key figure in the SPG and spoke on its behalf in the house of Lords. He also became its president, taking the place of Archbishop Wake and doing what he could to advocate for ministers abroad. In 1725 Gibson put a plan and request before the Privy Council for suffragant bishops to be sent to the mainland colonies and the islands, but it was not approved.

Despite these evangelical concerns, Gibson remained a defender of the slaveholders’ financial interests. He supported clergyman George Berkley in publicising the 1729 Yorke Talbot judgement that the enslaved would not become free once in Great Britain, or through baptism. The ruling was that

“a Slave, by coming from the West indies to Great Britain or Ireland…doth not become free”, “that Baptism doth not bestow Freedom on him, nor make any alteration in his temporal Condition in these Kingdoms”, and that, “his Master may legally compel him to return again to the Plantations”.

When Gibson died in 1748, the position of the commissaries had not much improved. Robert Jenney, his commissary in Pennsylvania, wrote to Gibson’s successor Bishop Sherlock explaining how little weight Gibson’s authority had, and by extension Jenny’s own as the Bishop of London’s representative:

“the patent of the late bishop did not seem to justify his commissary in any juridical proceeding: the laity laughed at it, and the clergy seemed to despise it, nor did there appear at home a disposition to show any regard to it. The commissary was not otherwise regarded than to be made the instrument of conveying letters, books, etc. to the missionaries, as he lives conveniently for that purpose in the chief place of commerce where the ships from us for London are for the most part only to be found.”

Arthur Holt , b. 1700

WARNING: This section contains some offensive language used in excerpts from original 18th and 19th century documents.

Arthur Holt was an Anglican missionary who worked on plantations in Virginia and Barbados, following in the footsteps of his father.

On 7 March 1728 he wrote to Bishop of London Gibson about the kinds of things enslaved Africans did as part of their obeah practices and what he thought of them:

“I should be glad to know your Lordship’s pleasure in regard to the infant negros born on the society’s [Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG)] plantations whether they ought not to have at least private baptism; publick baptism would indeed be impractiacable because of the want of suretys.

It is a thing heartily wished by all good Christians that sufficient care was taken to retrain the negroes of this island and especially those on the society’s plantations from what they call their plays (frequently performed on the Lord’s days), in which with their various instruments of horrid music, howling, and dancing about the graves of the dead, they offer victuals and strong liquor to the souls of the deceased to keep them (as they pretend) from appearing to hurt them … in which sacrifices to the enemies of souls the Obys or Conjurors are the leaders, to whom the others are in slavery for fear of being bewitched from whom they often receive charms to make them free of … in any villany … while these things are permitted, Christianity is likely to make but slow advances here.”

Holt’s letter demonstrates the colonisers’ view of traditional African practices: seeing them as primitive and irrational without attempting to understand their cultural importance. On the whole, the letters from Anglican ministers demonstrate a negative attitude toward obeah, seeing it as a form of witchcraft, and therefore incompatible with Christianity.

Holt did, however, criticise the physical punishments and measures meted out, writing to Bishop Gibson and the SPG to complain that enslaved Africans on the Codrington estate were branded with the word ‘SOCIETY’ so they could be found and returned if they ran away. It is not known whether his appeal had any effect.

Beilby Porteus, Bishop of London 1787 - 1809

WARNING: This section contains some offensive language used in excerpts from original 18th and 19th century documents.

Family background

Porteus’s grandfather Edward Porteus (d. 1700) and father Robert Porteus (1679 – 1758), owned plantations in Virginia, North America. Evidence from their wills show that the family were enslavers, both within their homes and on their plantations. Edward Porteus named two house servants in his bequest to his wife, apparently an indentured white woman and an enslaved African young woman or girl. It also highlights the fact that the English woman would eventually be free to leave her position after a certain number of years, while the enslaved Cumbo was a possession who had no such rights or expectations.

“To his wife his horse Jack with her saddle and furniture; also her clothing and his largest silver tankard and caudle cup, a featherbed and furniture, the time his English servant maid Betty has to serve, and his Negro girl Cumbo”.

A caudle cup is named after a warm drink made up of eggs, bread, oats, mulled ale or wine, milk, and spices. The wine and spices are another indication of Edward’s relative wealth. Edward also refers to the enslaved Africans and servants who worked his New Bottle plantation. He stipulates that they should be kept and the tobacco they produced be sent yearly to England.

Edward Porteus was one of the first members of Petworth County (sometimes Petsworth, also Petso), Gloucester County, Virginia, buying 500 acres from Thomas Lane on 16 March 1674/5. Gloucester Town itself was later laid out into lots and streets with Edward Porteus listed as the owner of the moderate-sized lot number twelve.

During the 1670s and 1680s enslaved Africans were taken to Virginia under the auspices of the Royal African Company under contracts arranged with London tobacco importers. Unlike in the West Indies, there was no public auction. Instead, this trafficking was “deeply intertwined with the consignment trade in tobacco that linked together larger planters … and the very same London merchants who made arrangements with the Royal African Company”. As a result, the elite had near-exclusive access to enslaved Africans. While their workforce “comprised almost entirely of slaves by the 1690s, somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of ordinary planters’ laborers were still white servants at the turn of the eighteenth century”.

According to the following records of letters sent to African Companies, Edward Porteus played a part in this elite trade and may have been well placed to acquire some of the enslaved Africans to work his own land:

“To Capt. Marmaduke Goodhand. 12 January 1685. Orders to sail in the Speedwell to James Island in the River of Gambia, collect at least 200 negroes, and take them to the Potomac River in Maryland for delivery to Edward Porteus, Christopher Robinson and Richard Gardiner. Mr Jeffery Jeffereys will pay for freight and care of the negroes.

To Capt. Marmaduke Goodhand. 23 December 1686. Orders to sail the Speedwell to James Island and collect about 200 Negroes for delivery to Edward Porteus or Christopher Robinson at York River, Virginia, according to the orders of Mr Jeffrey Jeffreys, who will pay for freight and care of the Negroes”.

Robert Porteus’ will also names an enslaved person, asking that “my poor old Slave Peter now in Virginia be freed from slavery and given comfortable maintenance…fit for one in his station”.

This does not necessarily mean that Peter had previously lived in England. There is no clear evidence indicating that Robert Porteus bought any enslaved people back with him when he moved the family to Yorkshire. Robert stipulates in his will that he wants his sons Edward (d. 1794) and Beilby to be his executors, that they should share the remaining third of the surplus between themselves and the children of his dead son Robert, and to direct the management or sell his estates as they see fit.

The 27 year-old Yorkshire-born Beilby Porteus, therefore, had a share in a Virginian plantation and was an absentee enslaver from his father’s death until the estate was sold.

In 1759, the New Bottle estate land was valued at around £600 and was little thought of. The enslaved workers and “stock” were valued at £1200 with a warning that their value in three or four years time would depend on the importation rate of enslaved people.

Beilby Porteus used his own will to ensure that his late brother’s land in Port Tobacco, Maryland “containing about two hundred and fifty acres”, should stay with his brother Edmund’s widow, Mrs Martha Porteus, for her life. Under the terms of his brother’s will, after Martha’s death the freehold, or “fee simple” went to Porteus who in his turn willed his interest “in remainder” to his great-nephew Thomas Porteus.

The town of Port Tobacco originated near a Native American village that Captain John Smith apparently named Potopaco in 1608. It was prosperous in the 18th and 19th centuries until the river filled with silt and the town declined. It was probably still thriving as an agricultural area with a large enslaved population when Beilby Porteus died.

In a 1790 census, Martha Porteus is listed as being a householder with nine enslaved Africans also living with her. In 1759 her land was valued at £50.

Gloucester County records were destroyed in fires during the Civil War and in the 19th century which impedes some of the research into the Porteus family but there may still be more to uncover.

Amelioration and abolition work

On 19 March 1784 Porteus, as Bishop of Chester, presented his plan for “civilisation and conversion” of the enslaved people on the Codrington Estate, which was owned by the Society of the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG). Much to Porteus’s disappointment, his recommendations were rejected and he realised that they would not consider improving the spiritual lives of the enslaved people for whom they were directly responsible:

“Thus was a final period put at once to this most important Business, & the Spiritual Condition of half a million of Negroes thus decided in the Space of four Hours. That the particular plan offered to the Society might stand in need of Improvement, & that another might possibly be have been substituted in its Room is very probable. I would have given my hearty vote for any such Plan in Preference to my own. It was not the mode It was the Measure I had at heart. But that the Discussion of this Subject should have been entirely finished at one meeting which everyone had expected would have taken up two or three, that no other Plan whatever should be adopted or proposed nor any one Effectual measure taken for the Conversion & Salvation of near 300 Slaves who were the immediate Property of a Religious Society did I own a little Surprize me.”

Porteus oversaw the 1794 emergence of the Society for the Conversion and Religious Instruction and Education of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies as its first president. It had little effect until 1824 when the West Indies had their own bishops who were able to push the agenda of the Society forward.

On 2 June 1795, the General Court of the Society for the Conversion and Religious Instruction and Education of the Negro Slaves in the West India Islands appointed two missionaries to be sent to Jamaica and Barbados. It also asked the Committee to prepare an abridged Bible and Book of Common Prayer which the missionaries could use: ‘Select Parts of the Holy Bible for the Use of the Negro Slaves in the British West India Islands’, published in London in 1807. It is not clear the extent to which Porteus was involved in selecting its contents, but he is listed as being present at an earlier Committee meeting on 27 April 1795.

In the same year, Porteus may also have contributed to the ‘Instructions for missionaries’ which the Society adopted. He was aware of the power the story of Christ’s Passion had to convert people, but also how it could be used to emphasise the need for enslaved people to obey their enslavers:

“It has been observed that nothing has so powerfully excited their attention, and touched their hearts, as the history of our Saviour’s life, miracles, sufferings, crucifixion, and resurrection, as related in the gospels.

With these, therefore, you must begin your religious instructions, and afterwards proceed to explain, in easy, perspicuous, simple, intelligible language, some of the plainest and most important doctrines and precepts of revealed religion; dwelling most strongly and most frequently on the necessity of faith in Christ, on the benefits derived from his death, on the truth and divine authority of the scriptures, and above all, on the great practical duties of piety, mercy, justice, temperance, charity, sobriety, industry, veracity, honesty, fidelity, and obedience to their master; contentment, patience and resignation to the will of Heaven.”

As Bishop of London, Porteus went on to become a lead supporter in the House of Lords of the 1807 Slave Trade Act which ended the British transatlantic traffic in enslaved people.

Porteus’s letter to the Governors, legislators and proprietors of plantations in 1808 tried to persuade them that educating and Christianising enslaved people would be to their own advantage. He explained that clergy and school teachers would work together to prepare a short form of public prayers for them, consisting of a certain number of the best collects of the Liturgy, the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments, together with select portions of the Scripture taken principally from the Psalms and Proverbs, the Gospels, and the plainest and most practical parts of the Epistles, particularly those that relate to the duties of enslaved people towards their masters.

Read the letter from Richard Corbin to Edward Porteus, 1759

Read Bishop Porteus’s will referring to Port Tobacco, Maryland

Samuel Ajayi Crowther (d. 1891), first African Church of England bishop

Samuel Crowther, a previously enslaved Yoruba man from Osogun (now in modern-day Nigeria), was made a priest by the evangelical Church Missionary Society. In 1864 he was consecrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury as bishop over African clergy in the Niger region of Africa. He was the second African-born man to be ordained, after Philip Quaque 80 years before him. According to author Travis Glasson however, by 1816 the Church and SPG struggled with the idea that African-born men could be legitimate members of the Anglican clergy. White Christians in Abeokuta and Lagos refused to serve under an African bishop.

Crowther translated the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer into Yoruba. His church eventually split from the European mission, and he became known as the father of the African church and the Yoruba people.