Acts of resistance & resistors

Enslaved Africans resisted in many ways before, during, and after their capture.

Sometimes these were in obvious ways such as fighting back through planned uprisings and sometimes they were through more covert ways, hidden from the white gaze. Click on the headings below to find out more about these different forms of resistance.

In Africa before enslavement

Before landing in Africa, the Spanish and Portuguese targeted the Canary Islands. Contrary to common assumptions, the indigenous people of the Canary Islands did not passively accept their Portuguese and Spanish invaders in the 1400s, but vigorously fought against them. The islanders used sharpened sticks and rocks “with enough force to knock an armoured knight off his horse”. And when the combined forces of Portugal and Spain attacked Tamara (now Gran Canaria) in 1468, the Tamarans used wooden swords and shields to beat the soldiers off. It was not until 1483 that the Spanish finally seized the island when Chief Tenesor Semidan surrendered and converted to Catholicism.

On board ship

Once forced on board ship, both women and men attacked their captors and attempted to escape. Women were often under-estimated as a potential threat and were left unshackled on deck. This meant they could watch for the best time to smuggle weapons to the men below and catch the crew by surprise. This happened on board the Robert of Bristol in 1721, when male African leader Captain Tomba used a smuggled hammer to release the captured men’s shackles and attack the crew. The attempt was unsuccessful, the enslaved African men were killed and the unnamed woman tortured until she died. Captain Tomba was still considered valuable enough to sell to an enslaver in Jamaica.

Captured Africans were more successful in 1730 when 61 women and 35 men took control of the Little George near the Guinea coast of West Africa and sailed it back to the Sierra Leone river. Although some were killed by the crew, many were able to escape on small boats. Although the remaining crew aimed their guns at the fleeing people on the coast, they were defeated by the fire power of the indigenous Africans shooting back at them and everyone was able to escape.

There were many other acts of resistance on board ship throughout the era of transatlantic slavery. Even though the transatlantic traffic in enslaved people had been abolished in England in 1807, and slavery itself in 1833, the trafficking of enslaved Africans was continued by other countries.

In 1839 the Spanish ship La Amistad was transporting 49 enslaved men and four enslaved children from Havana to Cuba. Led by Joseph Cinqué, Faquorna, Moru, and Kimbo, the enslaved African men overtook the ship, killed a few people, assumed control and put their enslavers in chains. They ordered the Spanish sailors to sail the ship who tricked them by veering off course until they were captured by a U.S. Navy ship and taken to New London, Connecticut and put on trial at the Supreme Court in 1841. The captured men and women were freed and apparently returned to Africa.

Individual acts of resistance

On the Codrington Estate

In 1712 the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), the missionary wing of the Church of England, inherited two plantations in Barbados from Sir Christopher Codrington: Codrington and Consett. Detailed archives kept by the SPG reveal how many enslaved workers ran to hide in the woods, away from the hard labour and bad conditions on the estate. Barbados had sloping woodlands rather than the mountains of Jamaica and so could not set up their own Maroon communities in the same way. Because of this, if people could not completely escape the island they often returned to the plantation they worked on after a few weeks away.

This happened when Churo and Jupiter escaped the Codrington estate in 1712. The accounts report that they both went away in a boat with a white man but a year later Jupiter returned, apparently “much rejoiced at the opportunity of getting back to his wife and children”. It is not known what happened to Churo.

In 1725 six people are recorded as missing, and in 1738, a group of enslaved people left the Codrington estate to ask the SPG for fewer hours, better treatment, clothes, food and a black overseer in addition to a white one. In return, they were publicly whipped and given further punishment the following day. The estate manager complained that the better an enslaved person was treated the more likely her or she was to resist.

Despite stricter rules being put in place for fear of anyone actively fighting against their enslavers, enslaved workers continued to run away, such as Dick Tober and Cubba in 1743 and 1745. In 1778 another group left to complain to the SPG. This time the estate overseer was sacked and better conditions apparently put in place. Escapes still happened however, with field worker Quashebah escaping several times in 1775, 1776, 1782, and 1784, even though she was taken back each time.

Letter from an enslaved Virginian in 1723, Lambeth Palace Library, FP XVII ff. 167-168

The writer of this letter appeals to the Bishop of London and King George to release them and their children from the bondage of slavery. The letter was written at a time when Virginian enslavers were starting to crack down on the freedoms and rights of both free and enslaved Black and mixed race people in response to recent uprisings. Punishments were extremely harsh. Enslavers at the time were often against allowing enslaved people to learn to read and write and this letter is an example of how doing so allowed enslaved people to argue for their freedom.

The letter writer mentions that ‘mulattoes’ like them have to remain enslaved even though they have either a white mother or father. At this time, a 1662 Virginian law stated that the “all children born in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother”. Therefore, if they were born of a free black woman, a child would also be free, whether or not their father was black or white. In practice however, most Black women were enslaved and any children therefore condemned to slavery.

In 1667 another Virginian law was passed declaring that baptising an enslaved person would not set them free. Previously, a baptised Christian was considered free, but as time went on the distinction for enslavers between religion and enslavement gave way to racial distinctions instead. Enslaved Christians, such as the writer of this letter, still equated baptism with freedom from slavery, much to the anger of their enslavers.

Women, childbirth, and healing

The contribution of enslaved women in uprisings has often been under-represented. As well as the bravery many showed in physical acts, sometimes in positions of leadership, they also resisted in more subtle ways. These included using their traditional knowledge of plants to regulate their family life and their own bodies. Stella Dadzie’s book ‘A Kick in the Belly’ demonstrates the many ways in which women fought against the repeated acts of terror and violence they were forced to endure.

While harsh conditions contributed to declining birthrates of enslaved women, they also took steps to manage and control their ability to get pregnant and give birth. In 1746 the Jamaican governor at the time, Edward Trelawny, wrote that abortion was the main reason for the lack of children. This might have been why only about six live children were born each year over 30 years. In 1809, planters took steps to improve conditions but the birth rate continued to decline. Much of this would have been due to the knowledge of medicinal plant-based recipes the enslaved women bought with them from Africa, including what to use to induce a miscarriage.

Other steps women could take were to use breastfeeding as a form of contraceptive, sometimes feeding their children for two or three years in order to space out their pregnancies. Enslaver John Baillee tried to reverse this in 1808 by offering mothers $2 to stop breastfeeding before the baby was 12 months old but records show that no one took him up on his offer. The effectiveness of women’s own agency in childbirth can be seen by what happened once European doctors left Jamaica. Despite the closure of hospitals and the increase in poor social and economic conditions, the birth rate rose to 40 births per 1,000 by 1840 compared to 28 per 1000 between 1817 and 1829.

Women also used their inherited stories and traditions to cope in their hostile environment, which, when combined with botanical and medicinal knowledge, were powerful means of resistance and agency. Women used this knowledge within their own communities and sometimes among white people too.

Cubah Cornwallis

Cubah Cornwallis (d. 1848) is known for her skill as an Obeah healer and nurse who cured the 20 year old Captain Horatio Nelson from various diseases, and later the future King William IV when he visited Jamaica. After she was freed by her enslaver, Captain William Cornwallis, she opened a hospital in Port Royal, Jamaica, and gained a reputation for healing throughout the Caribbean, becoming known as ‘Queen of Kingston’. Little is known about her origins but there is an oral tradition that she might have been born a Ashanti from Africa.

Mary Seacole

Mary Seacole (1805 – 1881), is another Black Jamaican-born healer. Mary learned traditional skills from her mother, a free Black woman, in the same way that enslaved women would have done from their own mother figures on plantations. As a free woman herself, with a Scottish army officer father, Mary travelled to England to learn Western medicine. She used her own money to set up the British Hotel near Balaclava during the 1853 – 1856 war in Crimea (now part of Ukraine) and provided care for injured soldiers.

Physical resistance and warfare during slavery

Throughout the period of slavery in the Caribbean, groups of enslaved individuals worked together to fight back against their enslavers. Sometimes this took the form of uprisings and guerrilla warfare, with attacks against people and property. Sometimes enslaved people ran away to form their own communities separate from the slave-based society.

First Maroon war, Jamaica, 1728 - 1740

When the British captured Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655, a group of enslaved Africans ran away to a mountainous area of the island where they could not be easily caught. They established Maroon communities consisting of free Black people, indigenous Taino, as well as enslaved Africans and enslaved Creoles who had escaped. These Maroon communities grew through raids on British plantations where recruits and supplies were seized and a series of uprisings amongst the enslaved people who joined them.

By the mid-1720s the Maroons were split into two main camps, the Leeward band and the Windward band, and posed a very significant threat to the whole system of exploitation. Experts in guerrilla warfare, the Maroons continually carried out raids on British plantations and successfully beat back attempts to dislodge them from their mountain camps. Furthermore, they were a constant encouragement to would-be rebels.

In 1740 a peace treaty was signed between the British and the Maroon leader, Cudjoe, which underlined that there was a ‘clear legal distinction between Maroons and slaves’. Nanny of the Maroons, or Grandy Nanny (c. 1686 – c. 1760), was probably present at the signing, and was described by hostage Captain Philip Thicknesse as wearing a belt with nine or ten knives hanging from it.

As part of the treaty, the Maroons were granted 500 acres of land in Portland parish but Nanny and her followers chose to break away and founded Nanny Town in the Blue Mountains. It was sometimes known as ‘Women’s Town’ since it was a safe place for women, children and non-fighting men.

As an Obeah* woman, Nanny mediated between the ancestors and the living in order to give advice and spiritually support the resistance of enslaved people. She is usually considered to be the original founder of the Maroon nation, from whom all Windward Maroons are descended. Her tribe is said to have been Kromanti from Africa, and Kromanti Play, made up of singing, dancing, and drumming, continued to form a vital role in the development of the Maroon community.

As well as Nanny, four male leaders were also considered founders of the Maroon community: Swiplomento, Welcome, Okonoko, and Puss. Their four tribes are usually referred to as Papa, Ibo, Mandinga, and Mongala which are also the names of four main styles of Kromanti Play. Much of this oral tradition has died out but the grounding mythologies helped the Maroons to form their distinct identity.

The popular image of Grandy Nanny/Nanny of the Maroons on the Jamaican $500 note shows her with a head wrap rather than a head tie. Colonel Harris of the Moore Town Maroon community wrote to the Jamaican Daily Gleaner in 1994 after the government issued the bank note with without consulting the Maroon community on her picture:

“A pall of sadness settles on our sensibilities at the realization that it is now almost a total impossibility for Jamaicans ever to visualise the invincible Chieftainess as she in fact appeared! Grandy Nanny did not wrap her head in that manner. She tied it. And the tying was consummated in a giant butterfly-knot at the back of the head. Evidence of this knot would be visible even from a full, frontal view”.

This except is taken from ‘True-born Maroons’ by Kenneth M. Bilby, pp. 192-3. In our exhibition at Fulham Palace we have used the same image Bilby did to illustrate one of Grandy Nanny’s descendants wearing a woman’s head wrap tied in the traditional Maroon manner.

* Obeah is a term applied to African spiritual traditions used by enslaved Africans and enslaved Creoles in British colonies in north America and the Caribbean.

Second Maroon War, Jamaica, 1795 - 1796

A dispute between some Maroons and a white planter was exacerbated by the attitude of the new Jamaican governor Alexander Lindsay, Earl of Balcarres, which led to a full scale war. The Maroons of Trelawny Town fought against the British, while those of Accompong Town (although connected to the Maroons of Trelawny Town by kinship and marriage) fought with the British. Even with their help, Balcarres had to resort to promising a treaty which he then dismissed as meaningless and deported about 600 Maroons to Sierra Leone. He tried other ploys with the Maroons of Charles Town and Moore Town who received intelligence before they fell into his trap.

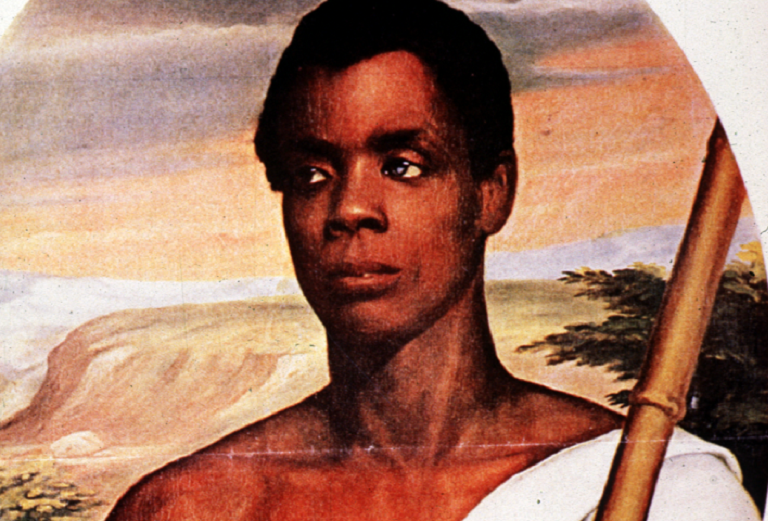

Takyi’s Rebellion, Jamaica, 1760 - 1761

Takyi led 100 enslaved people to seize arms and ammunition from Fort Haldane in the parish of St Mary. Likely from high military rank from Accra, his name means ‘someone royal’ in the Ga language. ‘Tacky’s Revolt’ is used as symbolic shorthand for what author Vincent Brown describes as a complex and confusing process which began on Fort Haldane and ended in defeat on the other side of the island. Another known leader was an enslaved Akan-speaking man called Apongo or Wager whose origins are unclear but who seems to have had military experience before arriving in Jamaica.

Haitian Revolution: 1791

Haiti was the first Black republic in the world to gain independence after sustained guerilla warfare by the enslaved population. Although they did not have many firearms at first, the fighters used their martial arts abilities, gained through years of stick fighting, to fight effectively with machetes.

Cecile Fatiman (c.1771 – c.1883), a Vodoo priestess, was a key figure in the revolution in the early stages when she used her relationship with the spirit world to galvanise and support the enslaved community in uprisings. She later married President Louis Michel Pierrot, becoming first lady of Haiti, and is said to have lived to be 113 years old.

Toussaint Louverture (c. 1743 – 1804) was from African heritage and enslaved from birth on the French colony of Saint Domingue. Despite this, he was given an education which led to his fundamental belief in universal human rights. According to author Sudhir Hazareesingh, Louverture was given his freedom from slavery by 1776, going on to join the enslaved fighters several years later. At first, he used his skills as a medic and physician but over time he became leader of the rebel soldiers, winning against the planters and French troops and keeping the Spanish and English at bay through diplomatic tactics.

Slavery was abolished on Saint Domingue in August 1793, a move which was followed by France in 1794 when all enslaved Black people in its Empire were granted freedom and citizenship. When Napolean seized power in 1799 however, he announced special laws for the French colonies and slavery was reimposed when he invaded in 1802 with 20,000 French troops.

Suzanne Sanité Bélair (1781 – 1802), was an Afranchi – a free woman of colour – and joined Toussaint’s army as an officer. She was executed by the French along with her husband, who was also an officer in the same army. The law at that time was for women to be decapitated but at the last moment she refused to be led to the block and was shot by a firing squad like other soldiers, and like her husband. She is a national heroine of Haiti.

Louverture was not killed, but died while held prisoner by the French a year before Saint Domingue became an independent country and changed its name to Haiti.

Fédon’s Rebellion, Grenada, 1796

This rebellion which took place as part of the French Revolutionary wars has been described by author Kit Kandlin as “…the single most destructive revolt against Britain’s rule in the Caribbean…”. It was inspired by the Haitian Revolution which broke out in the French colony of Saint-Domingue four years earlier. The uprising was led by the free-coloured population, particularly Julien Fédon (d. c. 1796) for whom it was named. However, it was the result of rising tensions between the island’s French and British inhabitants, as well as the abuse and mistreatment of the enslaved labourers who made up most of the combatants on both sides. Grenada had only been in British possession for roughly 30 years, having been ceded during the settlement of the Thirty Years War. Over that time, considerable tensions between the two groups were exacerbated by the discrimination of Catholics and ‘free coloureds’ (most of whom were French speaking), by the British.

Bussa’s Rebellion, Barbados, 1816

Bussa led the rebellion with the help of other members of the community. He was an enslaved ranger on the Bayley plantation, which meant he looked after the boundaries and could travel between estates. In this way, he was able to plan the initial uprising with senior enslaved people from other plantations. These included a driver called Jackey, a carpenter called King Wiltshire, and Nanny Grigg, a house servant.

The enslaved thought that they were going to be freed when the governor of the island, Governor Leith, returned from a trip away and were angry when this did not happen. Nanny Grigg is said to have persuaded others to fight for their freedom instead, using the successful revolution on Saint Domingue/Haiti as an example. Bussa led 400 women and men against British military forces but the rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful and ruthlessly ended by the army, who killed many in battle and executed more afterwards. However, the uprising left enslavers feeling insecure and enslaved people increasingly unhappy in Barbados and throughout the Caribbean.

Demerara Rebellion, present day Guyana, 1823

Around 1809, British missionary John Wray arrived at Bethel Chapel on the Dutch-owned Le Resouvenir estate. He was sent there by the London Missionary Society to preach the gospel. While there, he also taught his enslaved congregation how to read and write. As a result, some went on to become clergy themselves, including a Ghanaian-born carpenter called Quamina Gladstone, who was baptised there and went on to become a well respected deacon. Quamina’s son Jack also learned to read and went with his father every Sunday to tell Bible stories to the other children.

Encouraged by Wray, Quamina and the other deacons read Bible passages which related to their situation, such as the fleeing of the enslaved Israelites from Egypt. Shortly afterwards, in 1813, the chapel was closed and Wray was forced to leave the island as the colonisers deemed it dangerous for the enslaved people to be converted to Christianity.

Four years later, Englishman John Smith and his wife Jane arrived in Demerara and were given permission to run the mission at Bethel Chapel as long as they did not teach any enslaved people to read. They did, however, make friends with the congregation, and made it clear that they did not agree with enslavement. When the insurrection started, though they were not involved in planning it, they decided to stay in their home rather than run away because they felt that they were not in danger from the enslaved people who knew them.

Demerara was known for being particularly violent to enslaved workers, and although the enslaved could complain in theory, in fact they often received worse treatment afterwards. Quamina and his son Jack ultimately decided that the only course open to them and their friends was to physically rise up against the colonisers, as had happened in Haiti.

Some of the enslaved thought that the British King had granted them their freedom which the colonisers were refusing to act on. They appear to have been influenced by John Smith’s sermons that slavery was un-Christian, and that violence towards another was wrong. During the uprising therefore, the enslaved fighters took care to use as little force as possible, using their writing skills to draw up a petition for the captured white people to sign, saying that they had not been badly treated or physically harmed. Despite this, military forces killed many of the enslaved and tortured many more.

John Smith was sentenced to death for inciting the rebellion through his preaching, and although the sentence was later retracted, he died in his cell. Quamina was executed on 16 September 1823 and is a national hero in Guyana. Jack was sentenced to death on 22 September 1823 but he was sent to the Caribbean island of St Lucia instead.

Baptist war (or Christmas Rebellion), Jamaica, 1831 - 2

This was the biggest bid for freedom by enslaved Jamaicans. Led by enslaved Christians, it was started by a fire on the important sugar-growing plantation, Kensington Estate, in the St James parish. Author Mary Turner talks about how converts used meetings and networks organised by the missionaries to plan their attack, something which the planters had long feared.

One of the most well known and prominent leaders was Sam Sharpe. He was an enslaved domestic worker in Montego Bay who learned to read and became a member of the Baptist mission and ‘ruler’ of the Native Baptists. He educated himself on what the Bible said about slavery, using it to argue that the enslaved should be free, as well as about the English campaign for emancipation. Both of these influenced his decision to persuade his congregation to work together to overthrow their colonisers.

He worked with other enslaved men who were skilled workers: saddlers, headmen and drivers who attended the Baptist chapel and led independent sects. Most of them were Creoles (born in the Caribbean rather than Africa). Their names were: George Taylor; John Tharpe; Dove; Johnson; Gardner.

The white establishment united and asserted itself, burning down mission churches in various waves of mob violence. The Baptist and Wesleyan missionaries could no longer continue as if neutral and were firmly identified as anti-slavery.

Samuel Sharpe was tried in a ‘kangaroo court’ where he was not allowed to speak and was later hanged. Author Tom Zoellner discusses whether Sharpe was a ‘violent radical’ or someone who primarily wanted freedom without hurting anyone but who could not control the actions of others.

Rebellions and wars after the abolition of slavery in Britain

Morant Bay Rebellion, Jamaica, 1865

Twenty-seven years after the end of slavery, conditions were still very poor for the previously enslaved Africans and Creoles. While they were ostensibly free, they did not have social, material, mental or cultural freedom. They were not allowed to own land but instead had to rent it from a white landowner for no more than a year at a time, and sometimes for less. This meant that they could not afford to plant crops like coffee which takes three years to be fruitful, or trees which would provide a yearly supply. Often, the landowner would give his tenant six months notice to leave the property just after the land had been planted. As a result, previously enslaved people were still dependent on white plantation owners for work and had to take whatever low wages were offered.

Paul Bogle, deacon of the Native Baptist church on the island, decided to stand up to the white rulers, asking for better treatment. Initially, in August 1865, he tried taking a list of complaints and requirements to the Governor Edward Eyre, but the governor refused to see the delegation and they returned empty handed.

Bogle then decided to take the matter further by organising and training people to fight. He was also influenced by previous anti-enslavement uprisings like Takyi’s war, where the rebels took part in bonding and strengthening ceremonies. This time Bogle and other rebels took part in ceremonies where they kissed the Bible and drank mixtures of grave dirt, blood, gun powder, or rum. By doing so, traditional African spirituality was mixed with Christianity.

Having prepared physically, mentally, and spiritually, Paul Bogle and hundreds of others marched to the Morant Bay court house in October 1865. This time, the crowd was fired upon, several white and Black people were killed, and the court house was burned down. Bogle captured the militia (policemen) sent to arrest him and wrote an appeal for fellow Black people to join in the struggle against oppression:

“It is time now for us to help ourselves; skin for skin; the iron bars is now broken in the parish; the white people send a proclamation to the governor to make war against us… war is at us, my black skin, war is at us, from to-day to to-morrow”

Bogle also thought the Maroon community would be on his side, but soon found that they were not. Instead, they kept to their agreed treaty, supporting the colonists, and captured Bogle, taking him to be tried under martial law. He was hanged in Morant Bay on 23 October 1865.

The white authorities brutally retaliated by killing many more people, including several women: Mary Ward; Justina Taylor; Letitia Geoghegan; Sarah Francis; Mary Ann Francis; Ellen Dawkins; and Judy Edwards.

A reign of terror followed, with the white colonisers reinforcing race-based social structures against Black Jamaicans.

The War of the Golden Stool, Ashante Confederacy, 1900 - 1901

Osei Tutu was the first King of the Ashanti Confederacy (now in Ghana, Africa) to establish the Golden Stool as a symbol of power and monarchy in 1701. The Ashanti fought several wars with the British who wanted control of the African Gold Coast, and in 1896 King Prempeh I was exiled to Sierra Leone when he refused to surrender. After four years of negotiation, the British again wanted the Golden Stool as a sign of their own sovereignty over the Ashanti people as well as tax payments.

In response, Queen Mother Yaa Asantewaa (1840 – 1921), by then in her 60s, rallied the chiefs to fight against the British, building stockades outside each village, and laying siege to a government building (Fort Kumasi) where about 3,500 British missionaries, government officials and their families were trapped.

In March 1901, Yaa Asantewaa finally surrendered to the British after learning that her daughter and some of her grandchildren had been captured. She was exiled to the Seychelles where she later died. She is a national hero in Ghana today.